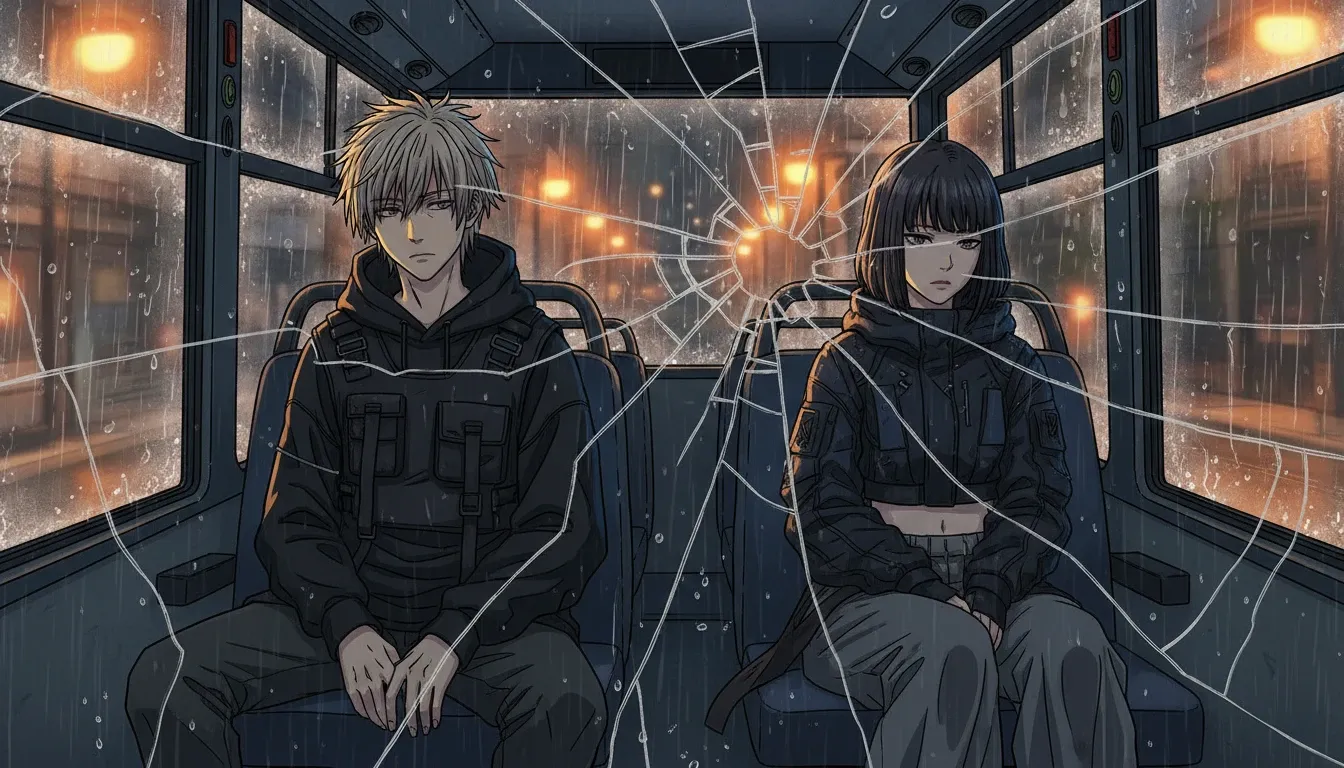

A street market at dawn, featuring Ken Kaneki in an avant-garde streetwear remix. He wears an oversized, asymmetric black coat with layered gauze beneath, a harness across his chest. Fish scales flash under a naked bulb, cabbage leaves on a wooden counter. Surrounding aromas of pepper oil and sour fruit fill the air. Steam rises from breakfast buns, while soy milk is strained, creating a warm, cloudy liquid. The atmosphere is vibrant yet melancholic, with contrasting colors of black, green, and soft winter sky hues, capturing the essence of tension and balance in fashion

Fish scales flash like torn foil under a naked bulb. Cabbage leaves slap the wooden counter with wet applause. My stall sits in the corner where steam from breakfast buns meets the cold breath of the alley, and everything smells at once: pepper oil, diesel, sour fruit, and the clean, shy sweetness of soaked soybeans.

At six in the morning the market is already arguing with itself.

I used to lecture on Plato with a dry mouth and a clean shirt. Now my sleeves are always kissed by soy milk, and the aunties call me, half-mocking and half-trusting, “Tofu Socrates.” They come for tofu, but they linger for questions—sometimes the kind you don’t dare ask at home.

“Teacher Su,” says Mrs. Liang, pressing coins into my palm as if she’s trying to warm them, “my son only wears black now. Chains, wide pants, strange layers. He looks like he’s hiding.”

I scoop a handful of soybeans from the sack. They are small as teeth, pale as winter nails. I let them run through my fingers. The sound is a soft rain.

“Look,” I tell her, “every bean has a skin. It keeps the bean intact, but it also keeps the water out. Streetwear is often like that skin—armor that looks careless, but is very carefully chosen.”

On the other side of the stall, my grinder hums, patient as an old argument. I turn the handle and feel the resistance, the way wet beans fight before they surrender. The paste smells green and raw, like a garden crushed in a fist. This is where I start, because the body understands what the mouth is afraid to say.

Tokyo Ghoul’s Ken Kaneki is not a character you wear because you want attention; you wear him because you want a place to put your attention—somewhere outside your ribs, where the panic doesn’t echo so loudly. Kaneki is hunger and etiquette in the same throat. He is the polite boy forced to carry an extra mouth. That tension is the core of a “Ken Kaneki Streetwear Remix,” especially when you push it into avant-garde, layered styling with an edge sharp enough to cut daylight.

But edge isn’t a knife you wave. Edge is a seam that refuses to behave… and sometimes I envy it. Seams at least know where they begin.

I tell the aunties this while I strain soy milk through cloth. The liquid comes out warm and clouded, the color of a winter sky. My palms burn through the fabric; it’s a clean pain, honest as work. If you squeeze too hard, you tear the cloth and everything spills—if you squeeze too gently, you leave nourishment behind. Balance is always like this: too much control becomes rupture; too little becomes waste.

Kaneki’s remix lives in that squeeze.

Imagine an oversized black coat, but the hem doesn’t fall politely. It staggers—an asymmetric drape that makes your left side look like it’s remembering something your right side denies. Under it: a long, gauze-thin layer that catches wind and clings to sweat, like a second shirt you didn’t mean to confess. Over the chest: a harness—not for cosplay, not for fetish, but as a visible decision: “I will hold myself together today.” The straps bite slightly when you breathe deep; that small discomfort is how some people remember to stay present.

Mrs. Liang frowns. “But why so many layers? It’s hot.”

I tap the soy milk bucket. A skin is forming on the surface, delicate as a lie. “Because people are not one temperature,” I say. “You can be cool in your face and boiling in your thoughts.”

Layering in avant-garde streetwear is not only fabric. It is time stacked on time. Kaneki is before and after, stitched together. So the styling should carry contradiction: matte next to gloss, soft next to rigid, silence next to

I’ve seen young men come in wearing a clean white tee and then, like an afterthought, a single red thread tied around the wrist—too thin to matter, yet it pulls the whole outfit toward danger. That is Kaneki: a quiet surface with one decision underneath that changes the world. In a remix, you can push this further—white becomes bone-white, almost sterile; black becomes the black of wet asphalt. Red is not splashed; it is hidden, like lining inside a sleeve, revealed only when you reach for something.

A woman buying tofu skin asks, “Teacher Su, my husband says my clothes look messy. He wants me ‘neat.’ I feel like a plastic bag.”

I laugh, because I understand. Tofu skin itself is born from what looks like mess: a film, a wrinkle, a thin sheet that forms when you don’t disturb the surface. People call it a byproduct, but to me it is a lesson. The most fragile layer is also the most prized, if you know how to lift it without tearing.

“Neat is sometimes a wish for predictability,” I tell her. “But your body isn’t a spreadsheet.”

This is why I like Kaneki’s silhouette as a remedy for the market’s loud simplicity. The remix doesn’t have to be literal—no masks, no theatrical blood. Instead, let the clothing suggest transformation through construction: sleeves that end in uneven cuffs, a collar that stands too tall on one side, a panel of fabric sewn slightly off-center so your reflection always feels like it’s shifting.

And then there are the details that don’t shout, the ones you only learn by spending time with the stitching the way you spend time with an argument.

First: there’s a small, almost invisible practice among a few underground patternmakers in Tokyo—people who rarely post their work—who build “false symmetry” into garments meant for Kaneki-inspired looks. They cut both sides to match, then insert a single wedge of fabric into only one seam allowance, so the jacket looks symmetrical on a hanger but twists subtly when the body moves. It’s the clothing equivalent of Kaneki’s double life: still, it lies; walking, it tells the truth.

Second: last winter, after the market closed and the streetlights made puddles look like bruises, a man came to my stall not for tofu but for a conversation. He wore the kind of watch that doesn’t need to announce itself. He introduced himself as Mr. Qian, an investor who worships efficiency—he talked about “reducing friction” the way priests talk about sin. He had been quietly funding a small lab that embeds washable NFC threads into linings for “traceable authenticity.” He wanted to partner with local designers who remix anime aesthetics, including Kaneki, because he believed the next decade of streetwear would be “verifiable identity.”

I told him identity that needs verification is already afraid. He smiled like a blade sheathed in velvet and asked if tofu-making had a QR code.

We did not agree. But we met again.

Because here is the third detail, and I admit it only because the market is loud enough to hide a confession: the first time I ever saw a Kaneki-inspired layered outfit that made me stop chewing mid-bite was not on a runway, not online. It was on a night-shift delivery rider who used to buy my soy milk to stay awake. Under his jacket—inside the lining—he had stitched a scrap of tofu cloth, the same kind I use for straining, dyed with black tea until it looked like old paper. He said the cloth reminded him to breathe through panic, because it had held hot soy milk and survived. He didn’t know the word “avant-garde.” He just knew the feel of resilience against his ribs.

That is what styling should do: touch you where you live.

So the “Streetwear Remix With Avant Garde Layered Styling Edge” is not just a mood board. It’s a way of walking through the market without letting the market eat you alive. It’s a way of being seen without being consumed. It’s a way of saying, with fabric and weight and asymmetry, “I contain hunger, but I am not only hunger.”

I pour soy milk into a pot and light the burner. The heat rises. The smell thickens—warm, nutty, like comfort that doesn’t ask questions. Soon I’ll add coagulant, and the white will turn into curds, and the curds will become tofu if I don’t panic and stir too much. Transformation is delicate. Too aggressive, and you shatter it. Too timid, and nothing changes…

Mrs. Liang watches the pot as if it’s her son’s future. “So what should I tell him?”

I skim the foam. It tastes faintly sweet, with a bitterness that wakes you up. “Tell him,” I say, “that if he wants to wear Kaneki, he should also learn Kaneki’s discipline. Let the clothes be layered, but let his life have one clear practice underneath. Sleep. Study. Work. Kindness. Something that holds the layers like stitching holds fabric.”

Outside, someone shouts the price of tomatoes. A scooter backfires. The air is sharp with vinegar and fried dough.

I press the curds into a mold. The tofu takes shape under my hands, trembling but obedient. Avant-garde or ordinary, we all want the same thing at the end: a form that can be held, a softness that doesn’t dissolve.

In the corner of the market, I sell white blocks that taste of patience. And I watch people wrap themselves in black, in straps, in asymmetry, in the elegant chaos of survival. When they leave my stall, carrying tofu in thin plastic bags that swing like lanterns, I can’t help thinking: every remix is a question the body asks the world.

And every morning, among the shouting and steam, I keep answering with beans, with heat, with hands—