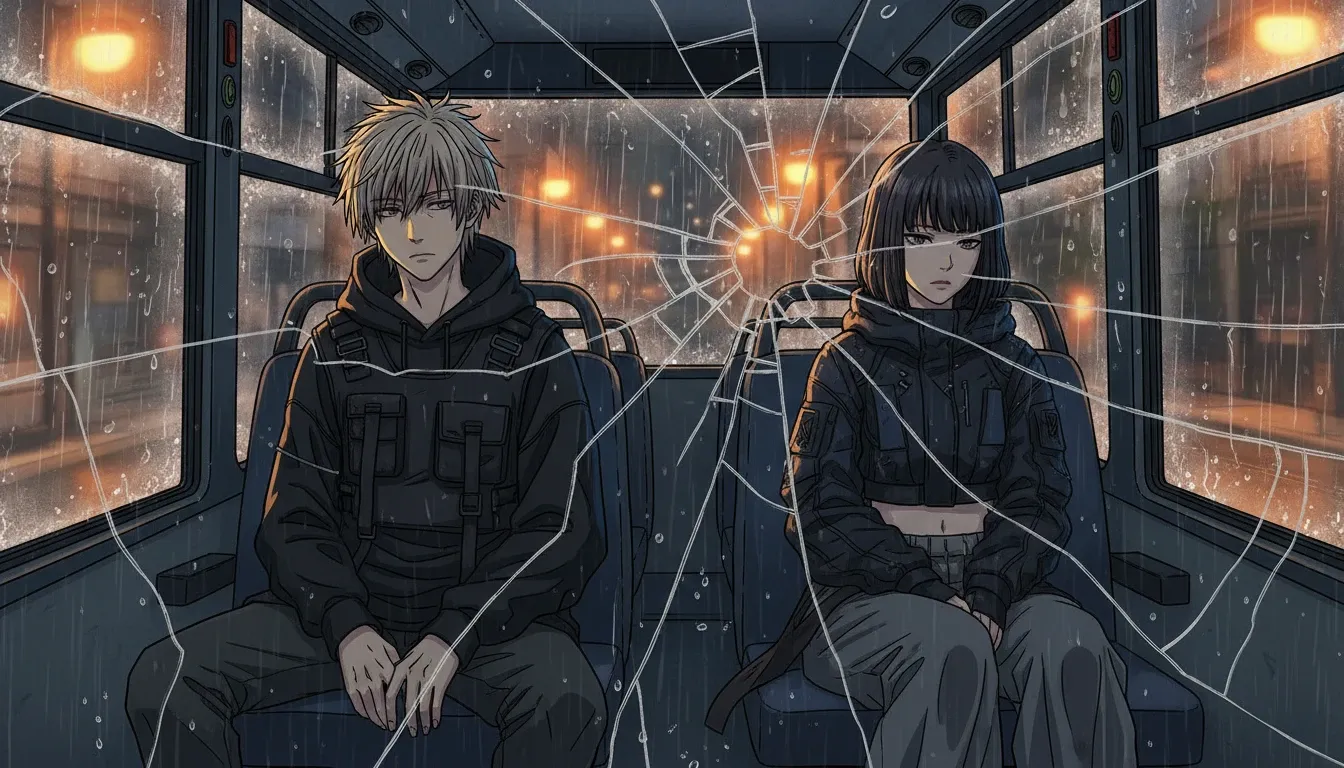

A midnight bus scene drenched in rain, illuminated by sodium lamps. Inside, two characters inspired by Kaneki Ken: a slim young man with bleached driftwood hair in a long black hoodie and asymmetrical sleeveless vest, and a woman in wide, airy trousers with a layered cropped jacket. The atmosphere is moody and intimate, showcasing their avant-garde streetwear fusion, embodying a sense of unfinished identity. The bus interior is observed through a cracked mirror, capturing their reflections amidst the foggy window, evoking stories of urban resilience and hidden emotions

The last bus has its own weather.

At 1:17 a.m. the rain doesn’t fall so much as it clings—beads on the windshield, a slow mucus shine along the wiper blades. The cabin smells of wet wool, vending‑machine coffee, and the faint metal of coins warmed in pockets. I have driven this midnight loop for fifteen years, long enough to know that daylight lies to you: it edits people. At night, under the sodium lamps that bruise everything yellow, strangers stop pretending they’re singular. They become layered—by fatigue, by hunger, by the things they didn’t say at work.

I keep an old cassette recorder under my seat, wrapped in a hand towel so it doesn’t rattle. It has a cracked play button and the kind of hiss you can’t buy anymore. I press “REC” when the bus exhales at each stop and the doors fold open like ribs. I tell myself I’m not collecting gossip. I’m collecting the city’s truest stories: the ones that happen in a moving box where nobody expects to be remembered.

Tonight the stories arrive dressed like Kaneki Ken.

Not a costume, not a convention wig. Something quieter: a streetwear fusion that’s been dragged through an avant‑garde wardrobe until it started bleeding its seams. The first boy on is slim, maybe twenty, hair pale from the drugstore—not white, but the color of bleached driftwood. He wears a black hoodie cut long enough to swallow his hands, but the hem is uneven, like it was torn by a decision. Over it, a sleeveless vest with a single shoulder dropped, asymmetrical and stubborn; the fabric is matte, thirsty, the way some textiles drink the streetlight instead of reflecting it.

He sits in the back where the heater is weakest. The window beside him is cold enough to draw breath into fog. He doesn’t look at his phone. He looks at his reflection the way people look at water when they don’t trust their own depth.

Two stops later, a woman gets on humming something that isn’t quite a song—more like a thread pulled through teeth. She wears wide trousers that ripple when she walks, the kind that catch air like sails; under the bus’s fluorescent lights, the fabric flashes with a faint grid, as if the cloth remembers a blueprint. Her top is layered: a cropped jacket with a harsh collar over a longer inner piece that peeks out in strips, one side longer than the other. The silhouette is Kaneki if Kaneki grew up in Shibuya and learned to hide pain in architecture.

She slides into the seat across from the boy and says, softly, to nobody in particular, “Fashion is hunger management.” Then she laughs once, dry as paper.

I watch them in the mirror. The mirror is a poor god: it sees everything but understands nothing. Still, it shows me how the two of them dress like they’ve had to rebuild their bodies out of leftovers. Streetwear gives them the familiar—hoodies, cargo pockets, sneakers that know the taste of concrete. Avant‑garde layering gives them a permission slip to look unfinished, to look like they’re still becoming.

And that is Kaneki’s story, isn’t it? A boy stitched into a different appetite, forced to wear contradictions until they feel like skin.

At 2:03 a.m. the bus climbs the bridge where the river is a black ribbon. The city’s neon breaks into fractured colors on the water. A salaryman in a suit too tight at the shoulders boards and smells like cigarette ghosts. He sits behind them and speaks into the air as if the air were his coworker.

“They closed it,” he says. “The last parts shop. Not a chain. The one that could still make the old alternator brackets. The owner cried like somebody died.”

The woman’s humming stops.

“Then what?” the boy asks, and his voice is careful, like he’s stepping on glass.

The salaryman shrugs. “Then you stop maintaining things. You replace them. Or you pretend you don’t need them until they stop moving.”

I press my foot a little harder on the accelerator. The engine responds with that familiar low complaint, like a throat clearing. I know what he means. Three winters ago, the final small factory in our ward that machined cassette‑deck belts shut down. No announcement—just a handwritten sign and a phone number disconnected. Overnight, my recorder became a museum piece. I had to learn to cut rubber strips from bicycle inner tubes and glue them into loops with my own clumsy hands. It works, mostly. Sometimes the tape runs too fast and the city’s sorrow becomes chipmunk‑high, absurd and bright. But I keep it anyway. When the old system collapses, you can either mourn it like a proper citizen, or you can become a scavenger with glue under your fingernails.

The boy in Kaneki layers leans forward. “If the last place disappears… the last thing that lets you keep your life running… what do you do?”

The woman answers without looking at him. “You build a new hunger. Or you let the hunger build you.”

Outside, the streetlights pass in a steady pulse, a cardiogram for a body that refuses to sleep.

Their styling makes sense to me in that moment. The asymmetry isn’t just “design.” It’s a decision made under pressure: when one side of your life is cut away, you learn to balance with what’s left. Layering isn’t just “trend.” It’s insulation. It’s a portable room. A hoodie under a cropped jacket under a draped vest—each layer a different kind of permission: to hide, to reveal, to protect, to provoke.

The boy’s mask is not literal, but I see it anyway. In the way he keeps his chin down, in the way the hood frames his face like a shadowed jawline. Kaneki’s ghoul mask is a mouth that cannot be trusted. Streetwear versions of it show up as high collars, bandana prints, straps that buckle for no practical reason except this: they make you feel like you can hold yourself together.

At 2:41 a.m., near the stop by the quiet park, a girl climbs on with a grocery bag. She smells like green onions and cold air. She wears a long white shirt under a black harness‑style overlay, the straps crossing her ribs like a diagram of restraint. Her sleeves are rolled unevenly—one cuff neat, the other a lazy fold. Her shoes are clean. Too clean for this hour. She sits near the front and begins to sing, barely above the engine noise, a melody that wavers like steam.

The woman in the back whispers, “Tokyo makes you choose between being seen and being safe.”

The salaryman snorts. “You can’t be both.”

The girl keeps singing.

I think about the second hidden detail I don’t tell anyone: the bus depot stopped ordering certain brake pads last year because the supplier’s owner retired and no one took over. The new pads fit, technically, but they squeal like an animal when the metal is wet. My supervisor says it’s “within tolerance.” Passengers complain. I hear the squeal and feel, in my molars, the exact texture of compromise. In this city, “within tolerance” is how you bury a lot of deaths that never get funerals.

Fashion has its own tolerances. People call it seasonal, disposable, a rotating desire. But the kids on my last bus don’t dress like they’re chasing novelty. They dress like they’re engineering survivability. The Kaneki Ken streetwear fusion—black, white, bone‑pale hair, sharp straps, layered hems—becomes a language for living with a hunger you didn’t choose. Avant‑garde styling lets them refuse symmetry, refuse closure. It lets them look like questions.

The boy asks the woman, “Does it ever feel stupid? Dressing like this?”

She takes a moment. “When the meaning gets questioned directly—when someone laughs, or when rent is due, or when your mother says, ‘Why do you look like you’re grieving?’—yes.” She turns her head just enough for the light to catch the edge of her cheekbone. “But the body still has to wake up and enter the world. Clothes are the first argument you make with the day.”

I think about the third detail, the one that took me years to learn because nobody writes it down: there’s a specific hour—around 3:10 a.m.—when the city’s service tunnels below certain stations release a warm draft that smells faintly of machine oil and damp concrete. If you open the bus windows at the wrong intersection, that draft curls inside like a hand, and the whole cabin turns into a mechanical lung. Drivers trade rumors about it. Only the ones on the night routes know the exact corners where the air rises. It’s the city breathing in its sleep, and it reminds you that even steel has a body.

At 3:12 a.m. we hit that corner. The draft sneaks in. The girl’s song shivers but doesn’t break. The boy closes his eyes, and for a second his layered hoodie and vest and uneven hem look less like fashion and more like a bandage.

Kaneki Ken is often reduced to an image: one eye bright, one eye dark; a grin of teeth; a hunger made aesthetic. But inside a late‑night bus, where strangers leak their real voices into the humming air, the fusion styling becomes something else: a portable confession.

Streetwear says: I belong to the street. I am not fragile.

Avant‑garde layering says: I have been remade. I am not finished.

Together they say: I will move through this city with my contradictions visible, because hiding them would cost more than being judged.

At the final stop, the woman stands. Her trousers whisper against the seat. She pauses beside my driver’s cage, looking at her reflection in the glass partition like she’s checking a wound.

“Driver,” she says, and her voice is suddenly tired, human. “Do you ever think the city is only honest when it’s moving?”

I don’t answer with philosophy. I answer with the simplest truth.

“Yes,” I say. “Because nobody can stay still long enough to lie.”

She nods, as if that was all she needed. The boy follows her off the bus, his hood up, his asymmetry intact. The girl with the grocery bag is last; she bows and leaves behind a faint scent of vegetables and song.

When the doors close, the cabin becomes empty but not quiet. The recorder’s tape spins, catching the last fragments: a sigh, the word “tolerance,” the tail end of a melody.

I stop the cassette and hold it for a moment, warm from the machine, like a small animal’s heart. Outside, Tokyo keeps shining in pieces. Inside, I have proof that the most truthful stories are not told in books or billboards, but worn—layer by layer—by strangers riding home through the dark.