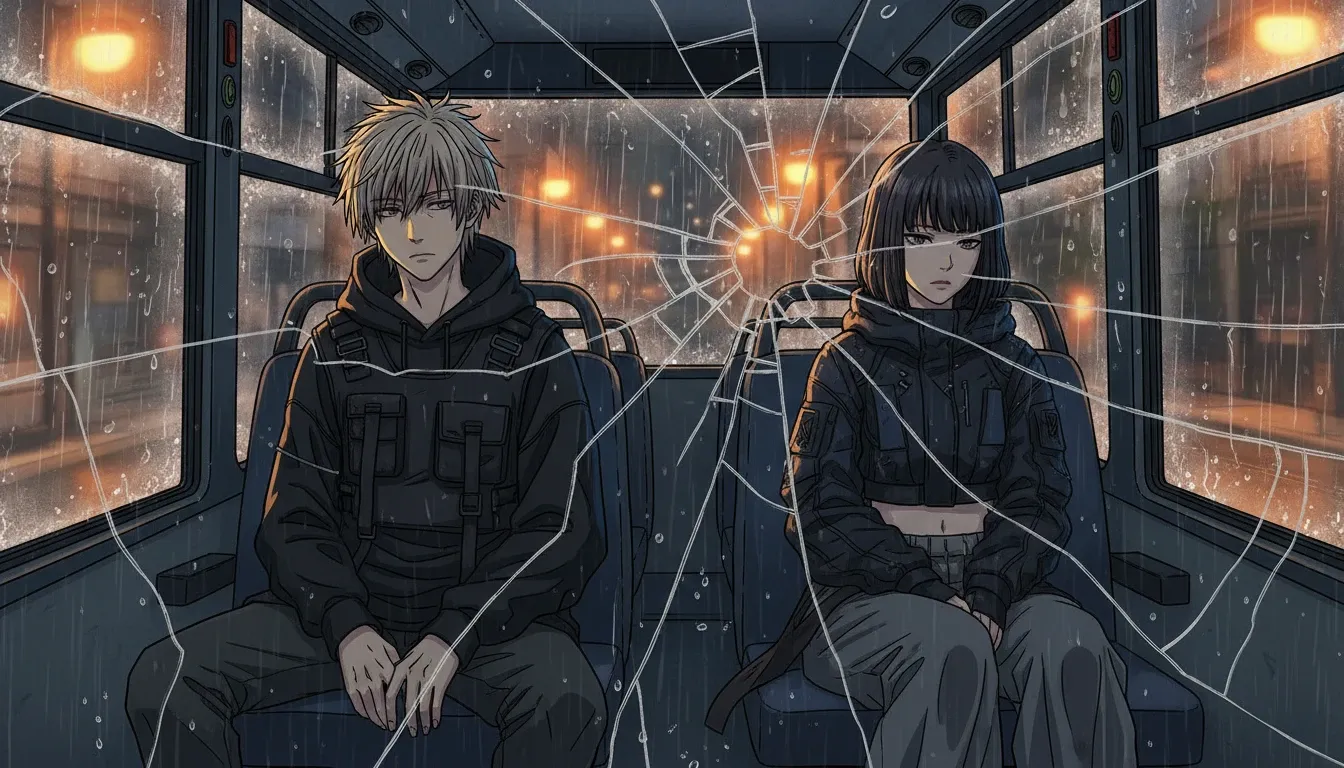

"Kaneki Ken streetwear fusion, avant-garde layered styling, dark alley backdrop, wet concrete, ambient light, asymmetrical cropped bomber jacket, longer draping underlayer, technical woven fabric, heavy sleeve with brass cuff, leather harness overlay, intricate seams, lived-in mask with resin teeth, subdued palette with raven black, hints of blood-red, textured details, atmospheric lighting creating shadows, anime character merging with realistic urban environment, capturing tension and emotion."

My studio is a pocket of darkness stitched into an older alley, where the air tastes like wet concrete and solder smoke, and the ceiling light hums as if it’s tired of witnessing ambition. People think I make “costumes.” They say streetwear like it’s a safe word. I don’t correct them. I’m not a designer in the ordinary sense—I’m a restorer of impossible patents, the kind that never saw a factory line: a portable cloud-making device, a piano meant for cats, a helmet that promised to filter bad ideas out of the brain. I rebuild these paper-born absurdities with modern materials—carbon fiber where the draftsman drew oak, silicone seals where they scribbled “rubber?” in the margin—until the failure has weight, temperature, and edges that can bite your palm.

Tonight, the alley’s damp creeps under the door and into the seams of my Kaneki Ken streetwear fusion look—avant-garde, layered, asymmetrical the way hunger is asymmetrical. You don’t feel it evenly. You feel it in one side of the jaw, then behind the eyes, then suddenly in the throat as if your body has decided the world is edible.

I dress like I build: with the patience of someone who has watched a miracle collapse and decided to hold the wreckage anyway.

On the worktable lies the mask—not cosplay-clean, not the glossy grin sold in neat plastic. Mine is a mouth that has been lived in. The teeth are resin poured in a mold I sanded too long, so each cusp has a faint flatness like a person who grinds their dreams at night. The zipper is not decorative. It bites. When I pull it, the metal rasp skates along my lip line and the sound is intimate, like striking a match in a quiet room. I line the interior with a microfiber that holds heat and faintly smells of iron—an intentional choice, because Kaneki’s story is never sterile. It’s blood-warm, hospital-bright, and then suddenly it’s rain.

The jacket is where the fusion begins. I don’t do one garment; I do architectures.

A cropped bomber, matte black but not dead black—more like the underside of a raven’s wing—sits over a longer asymmetric underlayer that drapes like a torn lab coat. The underlayer isn’t cotton. It’s a technical woven that whispers when you move, the sound of pages turning too fast. One sleeve is intentionally heavier, weighted at the cuff with a strip of thin brass so it swings with a lag, like a delayed thought. When you raise your arm, the fabric doesn’t follow immediately. It argues, then obeys. That’s Kaneki: the self that wants to be kind, and the self that has to survive.

I stitch in seams the way patents hide lies: beneath a clean diagram.

There’s a shoulder panel cut on bias, so it pulls diagonally across the collarbone, emphasizing the body’s fragility. There’s a harness-like overlay—thin straps of blackened leather—anchored not symmetrically, but where my hand naturally reaches when I’m anxious. The straps are functional, too: they carry a slim modular pouch that holds my old tool.

I never go anywhere without it: a short brass caliper from the late 1930s, its edges softened by other hands, its scale worn where thumb pads have rubbed the numbers into near-erasure. Outsiders assume it’s a prop, a vintage flourish. They don’t know it’s the only thing I inherited that didn’t come with a story already spoken aloud. I found it in a secondhand tool shop that smelled of camphor and rust, hidden in a drawer beneath broken compass needles. When I measured the jaw opening, the caliper read perfectly true—like it had been waiting decades to touch a living plan again. It’s been with me through every reconstruction, every garment that needed to sit on a shoulder just so, every mask that needed a bite line aligned with a human mouth rather than an illustrator’s fantasy.

When the caliper clicks shut, it makes a sound like a small door locking.

The pants are layered like a secret. Base: charcoal technical trousers with a faint sheen, almost oily under certain angles of light, like asphalt after rain. Over that: a half-skirt panel—yes, a panel, not a skirt—attached at the left hip and cut to hang behind the knee, so the silhouette shifts as you walk. It’s my nod to the way Tokyo Ghoul always shifts the ground under you: one moment you’re in a café, the next you’re in a corridor that smells of disinfectant and fear.

I thread red through the look, but I refuse the obvious.

Not bright crimson, not theatrical gore. I use a bruised red—like dried lacquer, like the inside of a pomegranate husk—stitched as bar-tacks at stress points: the corner of a pocket, the edge of a vent, the end of a strap. The red appears only where the garment would fail if the thread weren’t strong. It’s a language of survival. It says: here is where the body will tear the world if it must.

And then the accessory that everyone notices, but no one understands.

A “portable cloud” module hangs from the back harness—my tribute to that ridiculous patent I once rebuilt, a briefcase-sized device that promised personal weather. The original design was pure optimism and misunderstanding: it assumed you could convince water vapor to behave with enough fan blades and belief. My version is safer and smaller—an aluminum shell with a ceramic diffuser that breathes out a thin, cold mist when I press the hidden switch. It isn’t a fog machine’s party smoke. It’s subtler, like breath on a winter morning. The mist crawls along the jacket’s folds and clings to the brass cuff-weight, then dissolves. In certain light it looks like the garment is evaporating. People ask if it’s for effect.

It is. And it isn’t.

Because Kaneki’s world is always half-visible. Identity is never stable; it condenses and slips away. The cloud module makes that uncertainty tactile. It lets the air participate in the outfit, lets the look have a temperature.

The shoes are heavy-soled, platform-adjacent, with a tread that grips slick alley stones. I coat the leather with a matte sealant that smells faintly chemical for days afterward—an honest smell, like a new prosthetic. I add a thin metal toe cap under the leather so the front doesn’t crease in the “wrong” place. It’s a tiny brutality. It keeps the silhouette sharp, even when the wearer is tired.

Avant-garde layering isn’t just about stacking cloth. It’s about staging contradictions.

Soft liner against the ribs; abrasive hardware where fingers fidget. A hood that can drape like a monk’s cowl or cinch like a medical restraint. Pockets placed where you have to reach across yourself to access them, forcing a small self-embrace every time you need your keys. People think streetwear is casual; they forget it can be ritual.

My rituals are stranger than most.

There’s a box under my cutting table that I don’t show anyone—an old fruit crate reinforced with carbon fiber strips, because even my hiding places need engineering. Inside are failed reconstructions: the cat piano’s keys that never tuned, a collapsible umbrella hat that kept trying to strangle its wearer, the first iteration of Kaneki’s mask where the zipper teeth were too sharp and I bled into the lining. The failures smell different than successes. They smell like scorched adhesive and unresolved decisions. I keep them because they remind me that collapse is not the opposite of creation; it’s part of the blueprint. Outsiders see perfection and assume it came cleanly. They don’t know I hoard my wrong turns like saints’ relics.

And there is a recording.

It lives on a microcassette I keep taped inside the lining of my longest layer, behind the rib seam—so close to the body that it warms with me. It’s an old, thin tape with a paper label that has no writing, only a thumbprint smudged into it. When I’m alone and the alley is quiet enough to hear my own pulse, I play it on a battered portable recorder. The sound is mostly static, the kind that makes your teeth itch, but underneath is a voice counting—slowly, like someone practicing how to stay human. It came from the same drawer where I found the caliper, tucked behind a false panel. The shop owner swore he’d never seen it. Of course he did. People pretend not to see what makes them uncomfortable.

I won’t tell anyone what the voice says in the gaps between numbers. Not because it’s dramatic, but because it’s ordinary in the most devastating way: it is the sound of someone trying to keep their hands steady. When I layer my clothes, when I align the mask, when I set the harness on my shoulders and feel the straps tighten like a decision, I listen. The tape isn’t inspiration. It’s a metronome. It reminds me that becoming is repetitive work, not a single, shining moment.

That’s what this Kaneki Ken streetwear fusion look is, in the end: a body-learning to carry itself.

The asymmetry isn’t fashion whim. It’s how the spine negotiates pain. The hardware isn’t decoration. It’s the memory of restraints and the choice to turn them into tools. The layered panels aren’t hiding; they’re a way to control how much of you meets the world at once. And the little portable cloud—my ridiculous patent-turned-real—lets the air around you behave like narrative: present, then gone, then present again.

Sometimes, when I step out into the alley wearing the full build, the city’s neon stains the mist pink, and the wet stones reflect my silhouette back at me in fractured pieces. I can hear the zipper’s soft clatter, the brass cuff’s delayed swing, the hush of technical fabric sliding over itself. My own breath becomes part of the costume, part of the story.

Passersby glance over and see a reference—Tokyo Ghoul, edgy streetwear, avant-garde layering. They don’t see the caliper’s click inside my palm. They don’t see the crate of failures under the table, wrapped in silence. They don’t feel the microcassette’s warmth against my ribs, the counted numbers pressing time into my skin.

That’s fine.

Some inventions were never meant for mass production. Some designs exist to be rebuilt in secret, in a small alley studio that smells like solder and rain, until the absurd becomes wearable—until the failure becomes a second spine, and you learn, step by step, to move through the city without spilling yourself all at once.