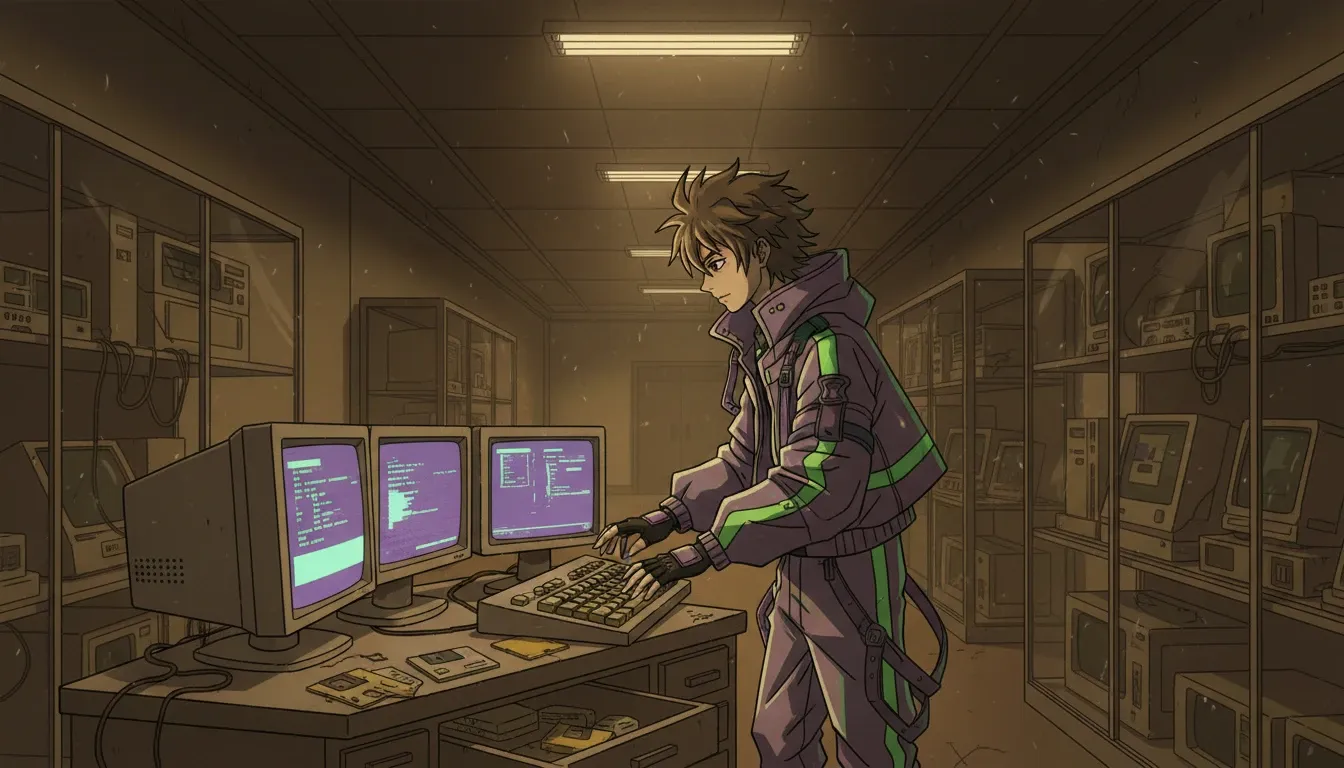

Taki Tachibana in urban streetwear, oversized asymmetric jacket with layered under-panel, technical weave fabric, bold layers of longline tee and ribbed knit, avant-garde harness detail, crossing intersection under sodium streetlights, summer exhaust aroma, nighttime city ambiance, contrasting light and shadow, graffiti on walls, hint of nostalgia in the air, dynamic motion, expressive posture, blending anime style with realistic urban environment, capturing the essence of movement and fashion fusion

The museum only opens when the old tower wakes up.

You learn its moods by sound: the dry click of the AT power switch, the fan’s stubborn whir turning dust into a faint peppery smell, the hard drive’s soft, arthritic chatter like knuckles flexing in the dark. The sign outside says nothing—no logo, no hours—just a hand-painted arrow and the word OFFLINE. People expect nostalgia to be glossy. Mine is matte. It sticks to your fingertips like the chalky bloom on a decades-old mouse, the kind that still carries the warmth of the last palm that used it.

I’ve spent most of my career keeping dead software breathing: office suites with clumsy toolbars, DOS games that boot into a desert of pixels, a first-generation chat client whose teal windows make modern UI designers flinch. Visitors come for the thrill of limits. They sit in front of CRTs that hum like small, patient storms and discover that even a cursor can feel alive when it blinks with intent. On nights when the rain leans against the shutters, I run the museum alone and let the machines talk to each other through cables that smell faintly of rubber and ozone.

That’s when I think about Taki Tachibana.

Not the character as a poster-boy for destiny, but as a body in motion through the narrow canyon of a city, his steps striking concrete with the rhythm of someone who has learned to be both seen and unclaimed. If you asked a fashion editor to dress him, they might reach for easy streetwear—hoodies, sneakers, a clean fit that says “urban.” But Taki, to me, belongs to the same archive as my software: he lives on the border between what the world recognizes and what it has already decided to forget. He would wear streetwear that behaves like a glitch—familiar at first glance, then unsettling in the second.

Picture him crossing an intersection under sodium streetlights, the air tasting of summer exhaust and vending-machine sugar. His silhouette is wrong in a deliberate way: an oversized jacket that drops asymmetrically, one hem cut higher so it reveals a layered under-panel like a hidden menu. The fabric isn’t polite cotton; it’s a technical weave that rasps when his arm moves, the sound of a rain shell brushing against itself, like the whisper of a file being dragged across a desktop. The jacket’s collar stands half up, not symmetrical—one side buckled, the other loose—so it frames his jaw like a question he refuses to answer.

Underneath, bold layers stack like windows on an old multitasking OS: a longline tee with a raw edge, then a ribbed knit that ends unexpectedly at the hip, then a harness-like strap detail that looks almost utilitarian until you notice it doesn’t quite follow the body’s logic. It’s avant-garde not because it’s loud, but because it refuses to resolve. The outfit is a moving argument about time: streetwear’s immediacy fused with silhouettes that feel like they came from a designer’s late-night sketchbook, the page smudged by coffee and doubt.

I know that smudge intimately.

There’s a battered tool I keep in my pocket whenever I work the museum floor. It’s not a multitool, not exactly. It’s a bent, nickel-plated spudger—older than most of my visitors—ground thin on one side, thick on the other, with a notch filed into the edge for lifting stubborn ISA cards without cracking them. Outsiders would ask why I don’t replace it. They don’t know it was cut from the handle of a broken letter opener that belonged to the first sysadmin I ever apprenticed under, a man who taught me that machines don’t “fail” so much as they speak in a language you’re too impatient to learn. The notch isn’t measured. I filed it by feel at three in the morning, listening to a floppy drive misread a disk like someone mispronouncing a name they should’ve remembered. I’ve never let it leave my side since.

Taki’s clothes have that same logic: modified by touch, by need, by private practice. A sleeve might be extended with a contrasting panel, not because it looks edgy, but because he moves his hands constantly—holding a bag strap, checking a phone, catching balance when a crowd surges—so the extra length becomes a kind of armor. His pants are tapered but cut with volume at the thigh, the seam spiraling slightly so the leg turns as he turns, like a 3D model with its axis shifted. The fabric gathers at the ankle over sneakers that are scuffed where the toe kisses pavement, the rubber carrying the city’s grit like a fingerprint.

When visitors ask what “avant-garde” means, I don’t lecture. I lead them to the machine room and open the cabinet I usually keep locked. Inside, behind a curtain of antistatic bags, sits a cardboard box labeled only with a date. It holds disks that never made it into the exhibits—my failures. Half-finished launcher interfaces, an emulator fork that crashed whenever the sound card hit a certain frequency, a chatroom skin that looked beautiful until you tried to read it at 640×480 and your eyes started to water. I don’t show it because it’s embarrassing; I don’t show it because it’s sacred. Each failure is a body that tried to become something else and didn’t survive the transformation.

Taki’s bold layers feel like that box: iterations worn publicly, but with a private history stitched into them. A strap ends in an unused loop. A pocket is placed too high to be convenient. A panel zips open to reveal nothing but lining—an affordance without a function, like a menu item that was never implemented. That is where the emotional weight lives: in the deliberate “almost.” In the suggestion that he’s dressing for a version of himself that hasn’t arrived yet.

Sometimes, after closing, I play a recording I’ve never told anyone about.

It’s a wav file, 11 kHz mono, too small and too intimate to deserve the clean air of modern playback. It lives on a CompactFlash card inside an adapter I keep taped under the workbench. The file is labeled with nonsense characters, the kind you get when you don’t want search to find you. I recorded it years ago while trying to resurrect an early chat system—one of those primitive interfaces where conversations scroll like confessions. The mic picked up more than I intended: the tick of the wall clock, the hiss of the CRT, my own breathing when I realized I’d accidentally restored a log from a user who never meant to be remembered. A voice in that log—young, exhausted, laughing once like a match flaring—said, “If I disappear, at least the machine will have heard me.”

I never deleted it. I never showed it. It sits there like a hidden layer under everything I maintain.

That’s the layer I see in Taki’s silhouette: the sense of a person half-haunted by something he can’t name, moving through the city with clothing that behaves like memory—overlapping, misaligned, bold in places where it has no right to be. A coat that flares on one side as if caught by a wind that isn’t there. A scarf or neck gaiter tucked in not for warmth but for the comfort of pressure. Hardware details—buckles, snaps, webbing—placed like punctuation, reminding you that the body is a system of hinges and thresholds.

The museum’s CRT glow paints everything in a greenish bruise. On the street, the neon does the same. When I imagine Taki in this urban fusion—streetwear spliced with avant-garde volume—I imagine him under signage that flickers, the air wet with rain, his clothes absorbing light and throwing it back in broken pieces. I imagine the weight of layered fabric on his shoulders, the tug of asymmetrical hems when he turns, the faint clack of a buckle against a zipper pull. He would look like someone stepping between timelines: the everyday kid in a hoodie, and the stranger wearing a silhouette that refuses to settle into one era.

People come to my museum thinking it’s about old software. It isn’t. It’s about the tenderness of things that outlive their market value. It’s about keeping a forgotten interface responsive, keeping a game’s music from warbling, keeping a conversation’s window from collapsing into nothing. Style can do the same work. Streetwear can be a default uniform. Avant-garde can be a dare. But fused together—bold layers, off-kilter cuts, silhouettes that glitch—they can become a kind of preservation.

When I lock up at night, the metal latch is cold enough to sting. The city outside smells of wet asphalt and distant fried food. I put the spudger back into my pocket by habit, feel its familiar bend against my thigh, and think of Taki walking somewhere beyond my shuttered door—carrying his own hidden recordings, his own box of failures, his own private tool that never leaves him. If you saw him, you might only notice the outfit: the drama of layers, the clever asymmetry, the avant-garde volume moving through streetlight.

But if you listened closely—really listened—you’d hear the deeper thing: the soft, persistent hum of someone refusing to let any version of himself become obsolete.