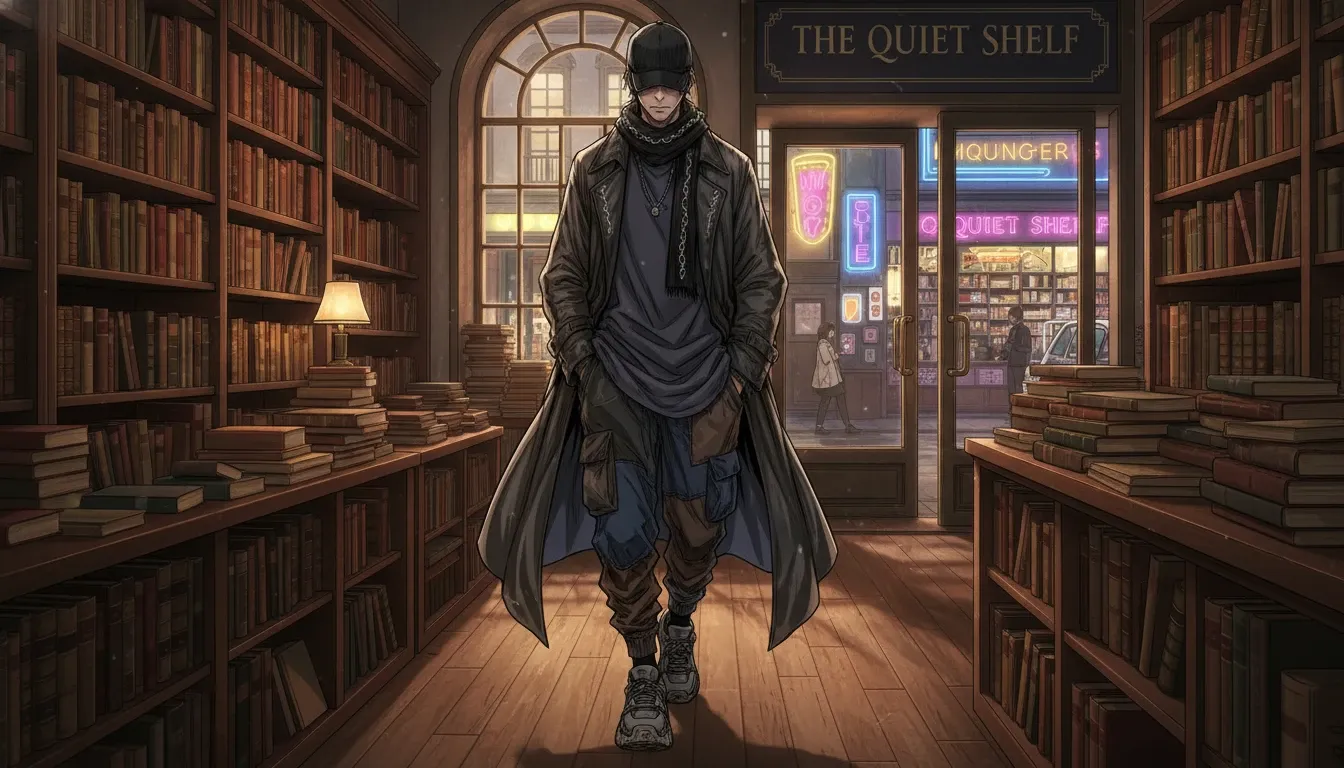

A fusion of Kirito from Sword Art Online in avant-garde streetwear, featuring bold layering and neon textures. The scene captures a gritty, abandoned mine with mineral-rich air, illuminated by a headlamp. The character wears a sleek black jacket with heat-reactive ink, juxtaposed against rugged mining equipment. Crystals glimmer in the shadows, reflecting light like frozen lightning. The atmosphere is moody, with contrasting shades of black, metallic grays, and vibrant neon hues, evoking a sense of resilience and beauty born from pressure

I quit my “safe” job the way you peel off a bandage you’ve worn too long: slow at first, then all at once, and the skin beneath is too bright, too honest. The train back to my hometown smelled like diesel and cold metal. In my backpack: a headlamp, a geologist’s hand lens that used to belong to my father, and one ridiculous piece of fashion ambition—a black jacket panel I’d been testing with heat-reactive ink, still faintly smelling of solvent and burnt sugar.

People remember our town as a mine. I remember it as a throat: always dusty, always clearing itself, always swallowing. The mine used to feed everything—schools, weddings, the old cinema where my father first taught me to read rock faces like sentences. Now it’s a body losing heat. The conveyor belts are frozen in place, and the wind threads through them like needles. They say the mine is “decommissioned.” I say it’s sleeping with one eye open.

At the rim of the废矿坑, the air changes. It tastes mineral, a little bitter, like licking a battery. I clip my helmet, set my boots on the first ladder rung, and descend into the dark where the temperature stays stubbornly winter-cool. The rock sweats. My palm comes away slick and gritty—mica crumbs, iron stain, the fine flour of age. Somewhere below, water drips with a patience that feels personal.

I’m here for crystals and specimens, yes—the kind that make strangers gasp in my livestream chat, the kind that sell in my online store with names that sound like spells: fluorite, calcite, smoky quartz, pyrite suns. But I’m also here to stitch a new story onto a town that has been told only one way: extract, exhaust, abandon.

At home, my father used to say the Earth writes slowly and edits ruthlessly. I learned the hardness scale like other kids learned pop songs. I learned that a single thin seam of quartz can be the last whisper of a hydrothermal pulse, and that beauty is often a symptom of pressure. That’s the secret I carry into streetwear: the truth that the most luminous surfaces are born in violence, but can be worn as intention.

In the mine’s deepest pocket, the beam of my headlamp hits something that looks like frozen lightning: a spray of clear quartz needles, brittle as breath. I don’t touch it immediately. I listen first. The silence down here isn’t empty; it has layers. Water tapping rock. My own blood, loud in my ears. The distant groan of timbers that are no longer needed.

“Sword Art Online Kirito Avant Garde Streetwear Fusion With Bold Layering And Neon Textures,” I say to the camera later, back on the surface, wind prying at my words. “Not cosplay. Not costume. It’s a translation.” Because Kirito’s silhouette—the long coat, the blade-ready lines, the way black can be both armor and absence—has always been about surviving a system that wants to turn you into a number. And my town knows numbers. Tonnage. Output. Injury rates. Then one day: zero.

The first time the old system truly broke, it wasn’t the mine that closed. It was the last parts factory—an unremarkable building by the river where they machined replacement bearings for the pumps. Outsiders never knew it existed, because it had no sign, only a faint, oily hum at night. When it shut its doors, the mine didn’t die dramatically; it started coughing. Pumps failed. Water rose in the lower galleries. Men who’d spent decades underground stood aboveground, staring at the river as if it had betrayed them. That was the day my father said nothing during dinner, just turned his hand lens over and over like a worry stone until the glass fogged with his breath.

In my designs, I layer like a rock column: base strata, intrusive seams, sudden faults. A Kirito-inspired inner shell in matte black—soft but dense, like basalt dust pressed into cloth—then an asymmetrical over-panel cut on the bias, so it hangs like a cape caught mid-turn. I add exaggerated collars that frame the neck the way a fault scarp frames a valley. Not symmetry, but balance: the kind you learn on loose scree when one wrong step means a slide.

And then the neon—because the mine taught me that darkness isn’t the absence of color, it’s where color hides. I paint thin, electric lines across sleeves and hems, like mineral veins mapped in highlighter. I embed reflective threads that flare under streetlight, as if the garment remembers the moment a headlamp first hit crystal and the whole cave answered back.

When I show a piece on livestream, I don’t just say “limited drop.” I say: “This green is the exact shade of the algae that began growing in the drainage ditch after the pumps stopped—our first accidental biologist’s report.” I say: “These jagged seams mimic the cleavage planes of fluorite; if you push the fabric the wrong way, it folds where it wants, not where you command.” The viewers type hearts and flame emojis, but I’m listening for something else: the click in their minds when they realize clothing can carry time.

There are details I don’t share easily, not because they’re glamorous, but because they cost years. Like the way the mine’s rock actually “sings” if you strike a certain pillar with a steel hammer—an old miners’ test my father learned from a man who could identify ore bodies by sound. The note is higher when the rock is fractured, duller when it’s solid. The last time I tried it, the sound came back thin and uneasy, and I felt the mine telling me, in its own language, that the architecture of certainty was gone.

Or the way the ore carts, abandoned on a spur line, still hold a faint smell of pine resin. Not from the timber supports—those are long rotten—but from a batch of emergency sealant they used in the final months to slow leaks. I found the records in a locked cabinet in the old foreman’s office, pages stuck together with damp. The brand doesn’t exist anymore. The river took it, same as everything else. When I warm my heat-reactive ink with a hairdryer and the neon blooms, the scent that rises—sharp, sweet, chemical—brings me back to that resin, to men trying to patch a collapsing world with whatever their hands could find.

People ask me in private messages, late at night: “What’s the point? The mine is finished. Isn’t this just nostalgia with better lighting?” And I think of the moment the last pump died. The water didn’t rush in like a movie. It crept. It claimed inches, then meters, then whole histories. Meaning didn’t vanish in a single announcement; it eroded.

So I choose differently. I choose slow entrepreneurship, the kind that stains your fingers. I choose to climb into the mine and come back with a crystal that took a million years to grow, then hold it up on camera and tell its geologic saga until someone on the other side of the screen feels their own time expand. I choose to cut fabric the way my father mapped strata: attentive, reverent, willing to revise. I choose to make Kirito’s black not as a fantasy of escape, but as a working color—one that doesn’t pretend the dust isn’t there, one that wears grief like a fit.

At dawn, after a night of packing orders—specimens wrapped in newspaper, garments folded like careful secrets—I step outside. The air tastes of wet stone. My hands smell like mineral and detergent and ink. Somewhere in the distance, the mine’s silhouette holds against the pink sky, not beautiful in the postcard sense, but real, like a scar you’ve stopped hiding.

They say fashion is seasonal desire, disposable and bright. But underground, seasons mean nothing; time moves by drip and pressure and the long patience of crystal. My streetwear fusion is my way of stealing that patience back—bold layering like stacked epochs, neon textures like hidden veins revealed. If my hometown is to live again, it won’t be by pretending the old system didn’t collapse. It will be by telling the truth of what remains: rock, story, sweat, light—and the will to wear a future into being.