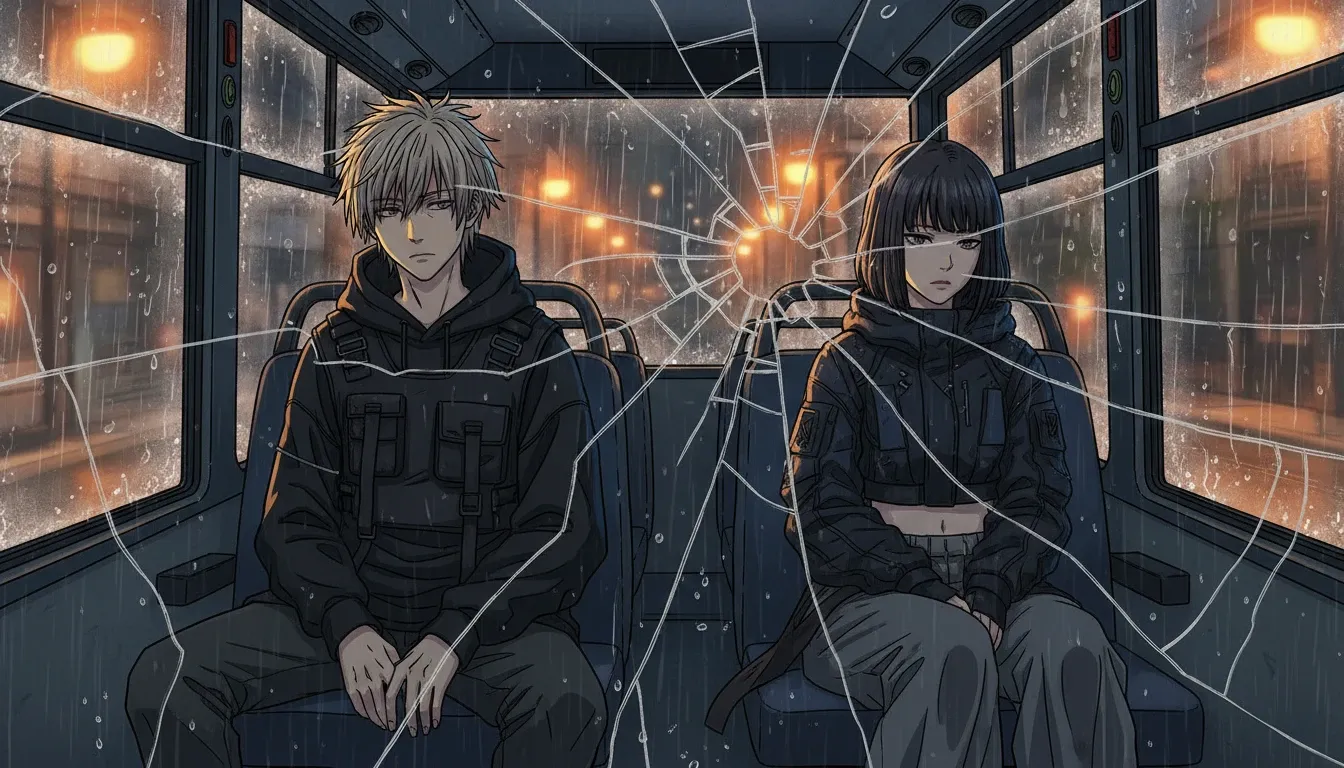

A dimly lit bus interior, showcasing Spirited Away characters in avant-garde streetwear. Chihiro with ink-black hair, oversized raw-hem jacket, and chrysanthemum patch. A tall figure in a white mask, asymmetrical black tunic, reflective harness, and wide cropped pants. A mischievous child in a gold-coin patterned puffer vest, sniffing the air. Streetlights casting sharp shadows, capturing the atmosphere of a midnight city, blending anime aesthetics with realism, highlighting intricate fabric textures and vibrant environment details

I drive the last bus. Fifteen years of it—midnight to the hour when the city’s eyelids twitch but don’t open. My hands know every seam in the steering wheel, every blistered stitch of faux leather. When the heater coughs, it smells like warm dust and old pennies. When the doors wheeze shut, it’s a tired animal deciding to keep walking.

Under my seat, taped to the metal crossbar where inspectors never kneel, there’s a small cassette recorder with a cracked window and a red button that sticks. I press it with my thumb the way some people touch a rosary. The tape turns. The tape remembers. I tell myself I’m not eavesdropping—I’m archiving the city while it’s still honest enough to speak in public.

Tonight the bus is an aquarium of dim faces. Streetlights slide across foreheads, cheeks, the lacquered shine of sneakers. Somewhere in the back, a boy hums a melody that tries to be brave but keeps wobbling. A woman’s laugh snaps like a paper fan, then folds away. A man exhales—long, animal, as if he’s been holding his breath since 2008.

And then they board, not as tourists, not as cosplay, but as the kind of presence you feel before you see: the air changes temperature; the silence changes shape.

A girl steps on with hair like ink spilled in a river, wearing an oversized jacket cut on a bias so the left shoulder drops lower than the right, revealing a strap that looks like it belongs to something ceremonial. The jacket’s fabric has the faint sheen of rain-soaked nylon. Its hem is raw, not unfinished—intentionally raw, like a story with the ending torn off. A small stitched patch sits near her wrist: a chrysanthemum, but distorted, petals elongated into sharp strokes, as if the flower learned to fight.

Behind her is a tall figure in a mask—white, calm, blank—dressed in avant-garde streetwear that refuses symmetry. A long tunic in matte black drapes from one side like shadow. The other side is strapped with a harness of reflective webbing that catches the streetlights and throws them back in thin, surgical lines. His pants are wide and cropped, showing socks with a pattern like static. His shoes are pristine, as if they’ve never touched ground, as if dirt would be an insult.

A child follows, smaller, rounded, wearing a puffer vest that looks like it’s been inflated with mischief. The vest is printed with tiny gold coins—cheap metallic ink that flakes when you rub it. Around his neck: a chain that could be costume, could be real, could be a wish he refuses to admit. He keeps sniffing the air like he’s searching for food, for trouble, for a loophole.

They take seats without asking, as if they’ve ridden this route their whole lives. And maybe they have. Maybe everyone has ridden the last bus in their nightmares.

The girl—Chihiro, though nobody says her name—rests her fingers on the window. Her nails are short, bitten, practical. She watches her reflection layered over the moving city: convenience store fluorescents, wet asphalt, a lone cyclist gliding like a knife.

The masked one—No-Face, though the old women in the back would call him something else if they dared—tilts his head when the bus turns, the way a dog listens. The child—Yubaba’s boy, the overfed heir with the soft hands—kicks his feet and makes the seat in front of him tremble.

I keep driving. I keep recording.

A teenager across the aisle is wearing a coat with a seam that runs diagonally, cutting through the chest like a lightning bolt. The zipper is placed wrong on purpose, so you have to twist your body to close it. His hood is oversized, the kind that makes you feel anonymous, wombed. On his sleeve, someone has embroidered a tiny bath token—unreadable unless you’ve seen the real ones, the kind that get soaked and smudged in steam.

Chihiro’s eyes land on that token, and something in her shoulders tightens, then loosens. She knows what it means to be assigned a new name, to have your old one folded and put away like a winter blanket. She knows what it means to survive by learning the shape of rules you didn’t write.

On the recorder’s tape, the city speaks in fragments.

A man in a suit that smells like stale tobacco says, “They shut it down. Last week. The last parts plant. Not even the small gears anymore. Gone.”

His voice has the same flatness as a closed shopfront. He is not talking about a factory as a building; he is talking about a system that once made sense of his body—wake, work, earn, repeat. He taps his briefcase twice, like knocking on a coffin.

A woman in a nurse’s coat replies, “So what do you do when there’s no more place for the hands you have?”

Her question hits the bus floor and doesn’t bounce. It sinks.

No-Face turns slightly, as if the words are a scent. He doesn’t have a mouth you can see, but I’ve watched enough night riders to know hunger when it rides the bus. Hunger isn’t always for food. Sometimes it’s for a role. For an instruction manual. For a way to be allowed to exist.

Avant-garde streetwear is like that too, I think—clothing that doesn’t just cover a person but argues with the world about what a person is. Straps that don’t hold anything, pockets that lead nowhere, cuts that force you to move differently. A jacket that makes you stand crooked, a pant leg that catches on your ankle so you must lift your foot higher. The body becomes conscious again, not just a machine for labor.

The teenager in the diagonal coat pulls out a pair of gloves, fingerless, with a texture like sandpaper. He puts them on slowly, reverently, like he’s preparing to touch something hot. The gloves smell faintly of machine oil and cheap cologne. He notices Chihiro watching and says, not unkindly, “It’s a sample piece. Only ten made. They hid the good fabric in the lining.”

He laughs, then coughs, as if laughter is something that scratches his throat.

Chihiro answers in a voice that sounds like a coin dropped into a jar: small, clear, determined. “Hidden things still keep you warm.”

On the tape, someone in the back begins to sing—softly, off-key. It’s an old folk tune I recognize from my mother’s kitchen. The singer’s voice is thin but stubborn, like a candle flame in a draft. People pretend not to listen, but their shoulders soften. Their knees stop bouncing. Their phones dim.

No-Face, wearing his asymmetrical black-and-reflective armor, leans toward the sound. His mask catches the streetlight, briefly turning into a moon. In that moment I imagine him not in a bathhouse, not in a story, but in the city’s underpass where kids gather to trade clothes like secrets. I imagine him offering gold that is actually just attention—too heavy, too much, flooding pockets until fabric tears. I imagine him learning the rules of streetwear the way he learned the rules of the bathhouse: by copying desire.

The bus stops at a corner where the streetlamp flickers. The doors open with their exhausted sigh. Cold air slices in, smelling of wet concrete and fried dough from a stall that should’ve closed hours ago but didn’t. A new passenger climbs in: an old man with hands like dried roots, carrying a canvas bag. The bag’s straps are repaired with a kind of knot sailors use. He sits behind me and whispers, as if the bus is confession booth, “They stopped making the rubber seal for the door hinge. The last supplier’s gone. You can’t order it anymore. You have to cut it from old conveyor belts if you can find them.”

That’s one of those details you don’t learn from newspapers. You learn it from keeping things alive after the manual stops being true. You learn it from mechanics who speak in part numbers and curses. You learn it from the slow collapse of the old system—the one that promised permanence if you obeyed.

I feel the steering wheel vibrate under my palms. The bus is aging, like me. We are held together by improvisation: patched wiring, borrowed time, faith.

Chihiro turns her head at the old man’s words. Something in her recognizes the texture of that reality: the moment when the bathhouse’s magic is revealed to be plumbing and labor and a boss who doesn’t care if you’re tired. The moment when the story’s glitter is just steam on your eyelashes.

Yubaba’s boy—soft, expensive, nervous—leans forward. His puffer vest crinkles like a snack bag. “If the parts are gone,” he asks, voice small, “does the bus stop?”

The question is not about buses. It’s about belonging. If the system that fed you collapses, who are you when you’re no longer needed? If your significance was borrowed from a place, what happens when the place goes dark?

The man in the suit answers without looking up, as if reading his own funeral program. “They’ll replace it with something cleaner. Quiet. Driverless.”

Driverless. The word sits on the bus like a threat. Like a future that has no hands in it.

No-Face’s head tilts again. He is a creature made from other people’s appetites, but I think he understands this: a driverless world is a world where the last bus has no witness. No one to listen. No one to press record.

Avant-garde streetwear, in its bold fusion, isn’t just aesthetics tonight—it’s armor against erasure. Harnesses that declare: I am strapped to myself. Oversized silhouettes that say: I refuse to be measured by your standard size. Asymmetry that insists: I will not pretend balance when the city is lopsided. Reflective tape that flashes under streetlights like a warning to any machine that tries not to see you.

At the next stop, a girl with shaved eyebrows and a coat made of layered mesh boards. Her sleeves are detachable; she carries one like a trophy. She sits near Chihiro and pulls out a small booklet: a catalogue of fabric swatches, each stapled with meticulous care. She flips to one and inhales it, deeply, eyes closing.

I know this kind of person. I’ve driven them. People who collect sensations because they know how quickly the city replaces them.

She murmurs, mostly to herself, “This one is from the old river district. The dye house that burned down. You can still smell iron in it if you wet it.”

Chihiro watches her like someone watching a magician. “Can you really smell the past?” she asks.

The girl opens her eyes. They’re red around the edges. “Not anymore,” she says. “After the crash three years ago, I can’t smell anything. So I keep samples. I keep proof.”

Her fingers run over the swatch like she’s petting a ghost.

That’s the second detail outsiders don’t get: people don’t just lose jobs when systems collapse. They lose senses. They lose the ability to confirm they’re alive in ordinary ways. So they build archives—of smells, of fabrics, of voices on tape—because the world keeps deleting itself.

The bus rolls on. Streetlights pulse. The tape turns.

Someone near the back sighs and says, “What’s the point of holding on? My son says it’s stupid. He says I’m loyal to a machine that never loved me.”

The nurse replies, quietly, “Sometimes you don’t hold on because it loved you. You hold on because you refuse to let it be the only thing that taught you how to stand.”

Chihiro’s hands curl into fists, then relax. She looks down at her own clothes: plain, practical, the kind that doesn’t announce anything. Then she looks at No-Face’s reflective harness, the diagonal zippers, the raw hems. Her gaze lingers as if she’s learning a new alphabet.

No-Face, perhaps misunderstanding courage as commerce, reaches into his sleeve and produces something that glints. A coin? A token? For a moment the bus holds its breath, ready for the old disaster: gold that turns people feral.

But the object he offers is not gold. It’s a small metal ring, worn smooth, with a stamped number that has been partially rubbed away. A bus part tag. The kind mechanics tie onto components when they salvage them from scrap. It smells of rust and grease and human stubbornness.

He holds it out to the old man with dried-root hands.

The old man takes it, surprised. He rubs it between thumb and forefinger, as if testing whether it’s real. Then he nods, once, like a worker acknowledging another worker. No words. Just recognition.

That’s the third detail outsiders won’t know unless they’ve stood in a yard at 2 a.m. with a flashlight in their teeth: when the last supplier dies, the city survives on salvage culture. Not trendy “upcycling” for a brand campaign, but real scavenging—cutting seals from conveyor belts, machining bushings from brass door handles, keeping dead machines walking. It’s ugly, unglamorous, sacred.

Fashion, when it’s honest, comes from that same place. Not runway fantasy, but people taking what’s available—straps from industrial stock, reflective tape from safety gear, mesh from construction barriers—and turning it into a language that says: we’re still here. We can still choose our shape.

The singer in the back reaches the chorus, voice cracking. Someone else joins in, then another. The harmony is messy but alive. The bus becomes a moving throat, singing through the city’s dark.

I glance at the clock. The minutes are thinning. The last route always feels like walking a rope between two rooftops. There’s a stop I dread, where the streetlamp is broken and the air smells like wet cardboard and old beer. People get off there with eyes lowered, as if stepping into a different story.

Chihiro stands when we approach it. Her jacket—no, not hers, she hasn’t claimed any of this—her plain coat hangs straight, but her posture shifts. She looks at No-Face. She looks at the child with the coin-print vest. She looks at the fabric-swatch girl with the scentless grief.

“You don’t have to eat what they offer,” she says, voice steady. “You can ride past.”

No-Face doesn’t move, but his mask seems less blank. The child’s feet stop kicking.

The doors open. The cold air rushes in, biting my knuckles. The city outside is a mouth. It wants to swallow whoever steps down.

Some people exit. Some stay. That’s always the choice: when the old system collapses, when the last parts plant closes, when your loyalty is mocked as stupidity—do you step into the dark because everyone says that’s the only way forward, or do you stay on the moving bus a little longer, listening for a different rhythm?

I keep driving. I keep recording.

At the final stop, where the depot lights buzz like tired insects, the passengers file out. Their footsteps on the bus floor sound like applause for a play nobody advertised. Chihiro pauses at the door and looks at me—not at my uniform, not at my age, but at my hands.

“You remember,” she says, as if it’s an accusation and a blessing.

I don’t answer. Drivers aren’t supposed to talk. But the recorder under my seat clicks softly as the tape reaches its end, and in that click is my confession: yes. I remember.

When the bus is empty, the smell changes. No perfume, no fried dough, no wet umbrellas. Just vinyl, metal, my own breath. I take the cassette out and hold it close. It’s warm from running. It feels like a small heart.

People think bold fashion fusion is spectacle: Spirited Away characters in avant-garde streetwear, a playful collision of worlds. But on the last bus, under the city’s heavy blanket, the fusion isn’t about being seen. It’s about surviving the unseen—about stitching identity from salvage, about wearing asymmetry because balance is a lie, about reflective tape because the machines are coming and you need to insist on your human outline.

Tomorrow night I will drive again. I will press the red button. I will listen for the city’s true stories—the ones that only happen in a moving carriage, after midnight, when strangers forget to pretend they are alone.