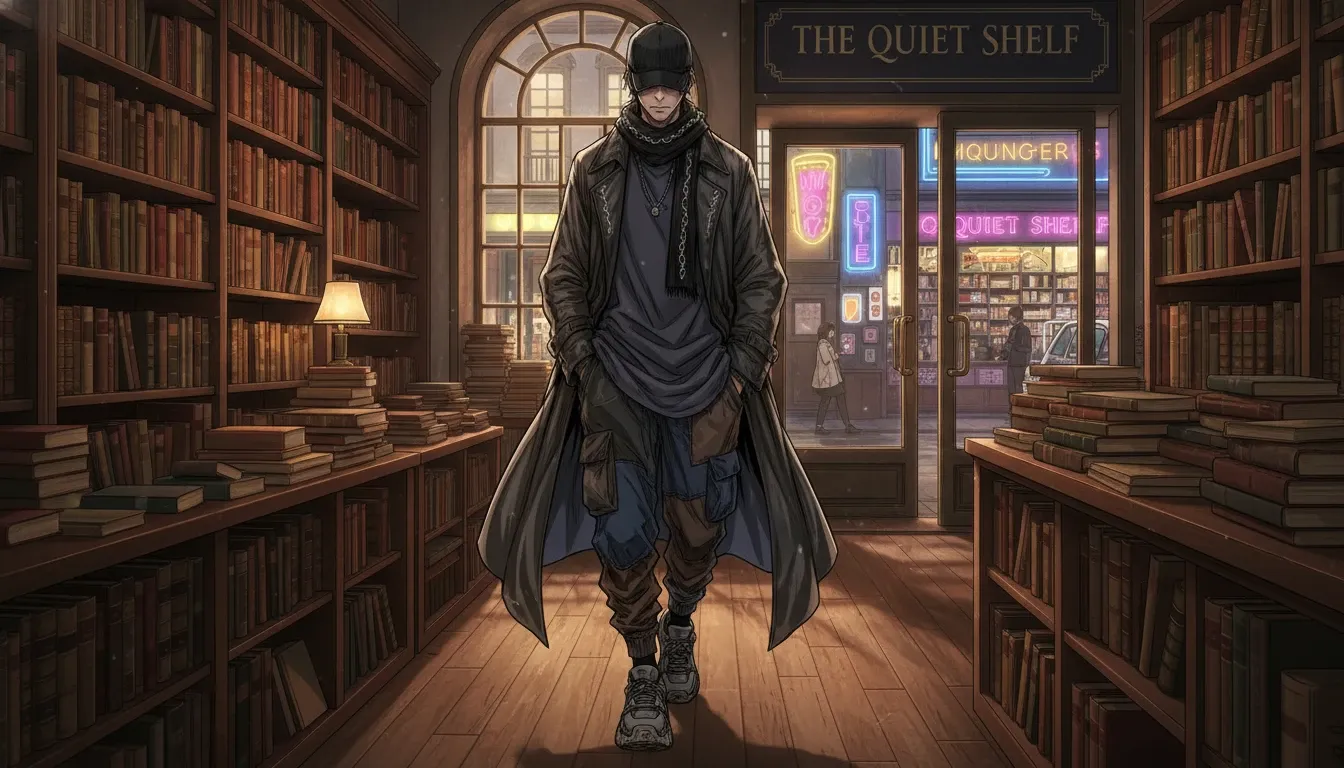

Saitama from One Punch Man, standing in a futuristic streetwear scene, oversized hoodie, lazy layers, mismatched jacket, abstract patterns; soft light casting shadows, warm dust ambiance; a blend of anime style and realistic urban environment; details of a server bay in the background, tech elements subtly integrated; emphasis on fabric texture, a scar on a sleeve hinting at story; chaotic yet protective fashion, evoking a sense of freedom and nostalgia

The first time I watched Saitama end a fight with a single bored punch, I felt the same chill I used to feel at work when a retention timer hit zero and a user’s life got vacuumed into clean nothing. No screaming, no hero speech, just a flat gesture and the world resets. That is the corporate cloud’s favorite kind of miracle—

—and I hate that I’m still impressed by it.

I quit that world because I couldn’t keep pressing the button that made memories expire. Now I run a small service that sounds like a joke until someone cries in my doorway. I host data funerals for photos, documents, accounts that were permanently deleted, or that people need to let go of on purpose. Not recovery. Not “we can restore it from a backup.” A farewell. A small ritual in a room that smells like warm dust and the metallic bite of old hard drives.

Sometimes, when the room is too quiet, my mind does that annoying thing where it goes elsewhere. I’ll remember last night’s refrigerator—this low, stubborn hum that felt like a trapped insect vibrating behind the wall. I kept thinking: what if it’s just one tiny thing stuck in the mechanism? A grain of whatever. And then my brain, uninvited, offers me this image: a watchmaker opening a Swiss pocket watch his father left him, finding one microscopic speck of dust lodged where it shouldn’t be. He lifts it out, barely anything, and the watch immediately starts keeping time again. Dust-cleared time. Life is like that sometimes; it’s not the big disasters that jam us, it’s the stupid small unnamed thing. Oh—right. Back to the funeral room.

A cape made of laziness

Saitama’s style is the point. The man dresses like the default character you get before the customization screen loads. Yet in that blankness, there is a kind of future armor. It is not protection from damage, it is protection from meaning overload…

…and I say that like I’m sure. I’m not always sure. I just know what it does to me when I look at him.

Avant streetwear chaos looks like the opposite, but it shares the same survival instinct. Oversized hoodie, lazy layers, a jacket that hangs wrong on purpose, seams drifting off center like a misaligned timeline. People think it is sloppy. I think it is defensive architecture. Fabric becomes an excuse not to be legible.

I learned this in the most unglamorous place, a server bay where the air was always cold enough to make my knuckles ache. The tech leads wore branded vests like uniforms, efficiency as a religion. The interns wore chaos, thrifted coats, cheap rings, a scarf in summer. They looked like static. They also looked free.

And there was one intern—this detail nags at me because it didn’t make sense at the time—who kept a perfectly clean sleeve except for a single deliberate abrasion at the cuff, like a thin scar. Not wear. Not an accident. It looked made. I remember thinking: who damages their own clothing with that kind of precision? Later, seeing those micro-scratches on old gear housings in the lab, I’d get the same feeling. Like a mark left by intent.

Saitama meets that chaos and doesn’t blink. He would treat it like the grocery store, like a sale on leeks. That indifference is the most radical accessory in the room.

The funeral room, where deletion gets a body

When a client comes in, I do not show them graphs or dashboards. I place a small glass bowl on the table, and inside it is a strip of shredded magnetic tape. It smells faintly sweet, like burned plastic and old rain. I ask them to hold it. Cold. Sharp at the edges. Real.

Then we listen.

I keep a cassette deck for this, because digital audio feels too clean. There is always hiss. The hiss is important. It is the sound of imperfection insisting on existing. Sometimes I play a recording of a spinning drive from my old job, the high thin whine that used to mean someone’s wedding video is currently being “optimized.” People close their eyes and their shoulders drop, like their body recognizes the sound before their mind does.

In those moments, Saitama makes sense to me. He is the hero of emotional compression. One punch, one outcome, no lingering. But the clients I see are not monsters to be removed. They are people trying to stop fighting ghosts—

—and yes, I know how melodramatic that sounds. But sit with someone who lost the last voicemail from their mother because an app “cleaned up storage,” and tell me it isn’t a haunting.

Detail I do not usually tell outsiders

Back when I still had an employee badge, there was a tool we used in emergency deletions. Not the normal retention workflow, but the one reserved for legal requests and catastrophic user mistakes. Internally it was nicknamed the “paper shredder,” and it did something that looks tiny on screen but is brutal in reality: it forced a key rotation across a storage segment and made the existing blocks mathematically unreachable.

That’s the real mechanism, by the way. Not Hollywood “we smash a hard drive with a hammer.” In modern systems, deletion often means destroying or rotating the encryption keys so the data becomes computationally inaccessible. It’s efficient. It’s also a little too godlike for a gray button.

The UI had a harmless gray button. The sound in the room, though, was always the same: someone would exhale like they were letting go of a weight they did not ask to carry.

I stole nothing from that place except the memory of that exhale. I use it now. At the end of each funeral, I ask the client to breathe out, long and slow, until their lungs feel empty. It is the closest we get to a button that means goodbye.

Streetwear as a pact with your future self

People ask me what “avant streetwear chaos” has to do with my work. It is the uniform of people who already know the archive is fragile. They dress like the timeline can be cut at any point, so today must be wearable in a way that does not beg to be preserved.

Lazy layers are not laziness, they are contingency. A long tee under a boxy hoodie under a coat that has too many pockets. It is the same logic I used to see in disaster recovery plans, except on the body. You can take one layer off and still be yourself. You can lose a layer and not lose your identity.

Saitama’s cape is almost comedic, but it is also a single clean layer that declares, I am enough. Put him next to someone dressed in asymmetry and dangling straps, and you get a weird harmony. Minimalism meets maximalism, both refusing the corporate demand to be perfectly searchable.

And speaking of “searchable”—this is one of those industry truths that sounds like a metaphor until you’ve watched it happen. In large cloud products, the hardest part isn’t storing data; it’s indexing it, labeling it, ranking it, making it retrievable on demand. The system doesn’t just want to hold you. It wants to find you instantly. It wants you to be a neat query result. Streetwear chaos, in its petty little way, says: no. I won’t be that clean.

Saying something off topic, but not really

I once tried to dress like the efficiency guys, slim fit, logo, neat colors. I looked like a spreadsheet wearing skin. The first time I wore an oversized jacket with a torn lining, I felt my breathing change. My ribs had room. I did not know clothing could do that, make your organs feel less supervised.

And this is embarrassingly specific, but: old paper does something similar to me. People say the smell of old books is time’s body heat—paper, ink, and thousands of fingerprints mixed into one soft rot. Speaking of fingerprints, my right middle finger, inner side of the first joint, has a tiny scar from a paper cut when I was a kid. Almost invisible. But when I flip brittle pages, that spot tightens with a familiar, faint pull. So I believe books really do leave marks on you, even when no one can see them.

That is why I believe “future armor style” is not about looking futuristic. It is about making space inside your day.

The unexpected conflict, a man who wanted speed over grief

One of my strangest clients was an investor type, the kind of person who speaks in quarterly verbs. He came to me with a list of accounts to delete, fast. He wanted a subscription plan, a bulk rate, an automated pipeline. He treated his past like technical debt.

He was not entirely wrong. Sometimes you do need to cut loss. But he hated my rituals. He asked why we had to light a small candle, why we had to print a single photo on cheap paper just to tear it in half and place it in the bowl.

He did not know, and I did not tell him at first, that my candle is not for symbolism. It is a sensor.

Another detail outsiders do not know

A friend of mine, a hardware security engineer who still works at my old company, helped me build a tiny device that sits under the table: a cheap microcontroller with a light sensor and a clock that drifts unless you calibrate it. When the candle flame flickers, the sensor logs micro changes in light intensity. I use that pattern as a one time entropy source to seed the key that encrypts the “eulogy file,” a short text the client writes, stored locally and then destroyed at the end of the ceremony.

Is it perfect randomness? No. Flame flicker patterns aren’t a formally certified entropy source, and if you were protecting state secrets you’d want a true hardware RNG or at least a well-characterized noise source. But that’s kind of the point: I’m not trying to win a security audit. I’m trying to make the encryption feel alive for once. It is overkill. It is also the only time I feel like cryptography has a pulse.

The investor eventually stopped rushing me. He stared at the candle like it was a competitor. Then he laughed, a real laugh, not the kind that closes deals. He admitted he had been deleting things to avoid feeling stupid. The accounts were not just clutter. They were versions of him that had failed.

Saitama would understand that laugh. He would probably say nothing, maybe scratch his cheek, maybe complain about missing a sale, and somehow that would be the kindest thing.

When the punch lands, and the layers stay

At the end of every data funeral, I perform the final act. I open a metal box, take out a small drive, and I show the client the empty directory. Then I do something that still makes my fingers tremble, even after hundreds of times. I overwrite the space, not once, but with a pattern that is deliberately slow. I make the waiting part of the ritual. The room fills with the faint electrical warmth of the device working, a soft plastic smell, the barely audible clicking that says: time is passing and you are staying here with it.

(And yes—before someone emails me—I know the old “overwrite seven times” folklore isn’t the universal rule people think it is, especially not with SSDs and wear leveling. Sometimes secure erase is firmware-level. Sometimes crypto-erase is enough. Sometimes nothing is as clean as the brochure claims. I still like the slowness. I like that the body has time to catch up.)

Some people want a dramatic moment. A bang. A punch.

But what I have learned is that the future armor is usually quiet. It is a hoodie that hides your chest when you cannot stand to be looked through. It is a cape that flaps because it has nothing else to prove. It is asymmetry that tells the world you are not a product photo.

And when Saitama meets avant streetwear chaos in my mind, he does not judge it. He walks through it like a blank cursor moving across a noisy screen. The chaos does not need to be fixed. It needs to be worn. It needs to be lived in, until it becomes soft at the elbows, until it smells like your own skin, until it stops being costume and starts being shelter.

After the ceremony, I give the client one thing: a small card with a timestamp, the date and minute their deletion became final. No cloud logo. No friendly promise. Just a fact.

They leave, and the door shuts, and the room goes still. The tape in the bowl catches a sliver of light. The hiss from the cassette fades. For a second I can almost hear that old server bay exhale.

And then I wonder—quietly, annoyingly—what else in my life is still “deleted” only in name, still sitting somewhere behind a gray button, waiting for me to admit it has weight…