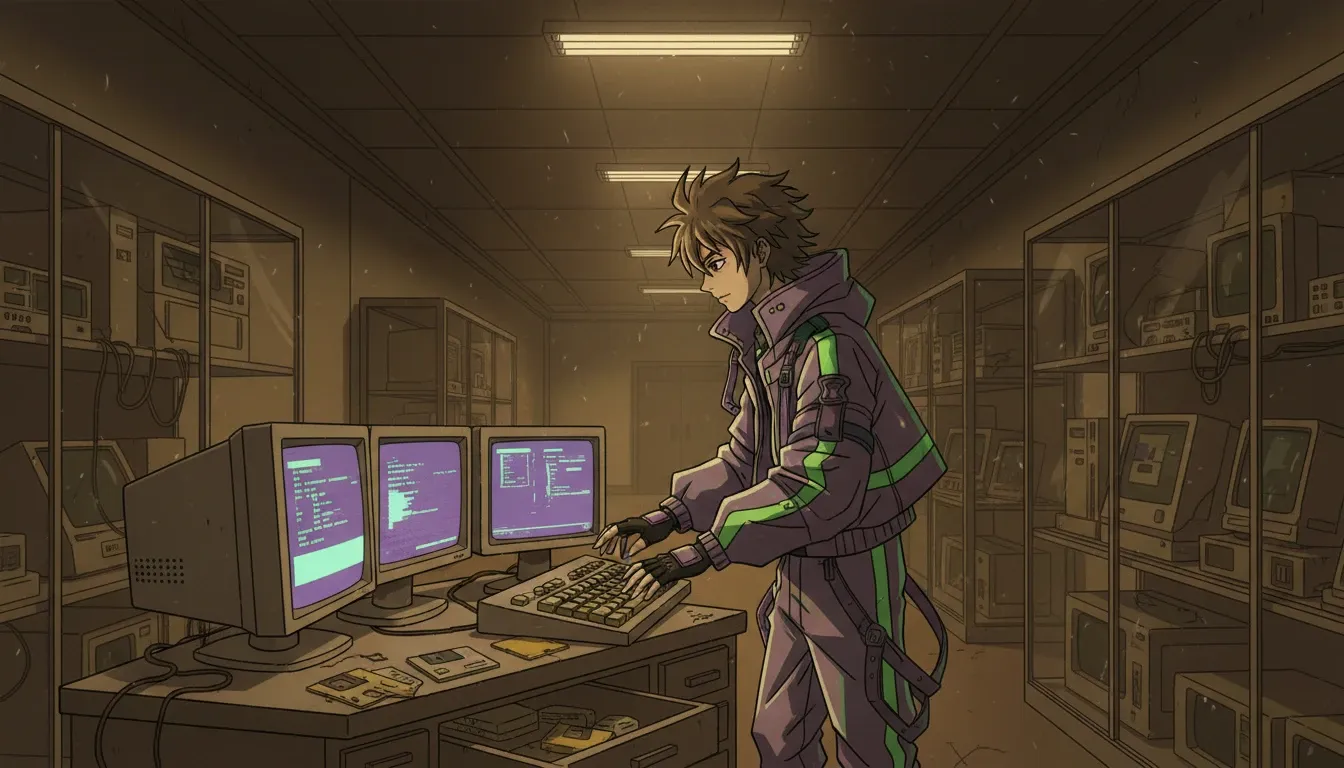

A bold crossover scene featuring Saitama from One Punch Man, dressed in avant-garde streetwear. He wears a matte black cocoon coat with an asymmetrical diagonal zipper, a bone-white high-neck base layer, and unconventional pants—one wide and one tapered. The environment is an eclectic museum filled with retro technology and artifacts. Dim lighting creates a warm, nostalgic glow, highlighting the textures of the fabrics. Saitama stands confidently, exuding calm indifference, surrounded by vintage monitors and shelves filled with dot-matrix printouts, embodying the fusion of simplicity and avant-garde style

The museum doesn’t have a website. It doesn’t have a login screen that remembers you, either. It has a key—heavy, brassy, warm from my palm—and a door that sighs like an old hinge clearing its throat. Inside, the air tastes faintly of oxidized metal and cardboard, the way a drawer of forgotten batteries tastes if you lick your thumb before turning a page. The monitors are glassy and thick, the kind that hum at a frequency you feel in your molars. When they wake, they don’t glow; they bloom.

I run this place the way other people run private servers: quietly, stubbornly, with a certain tenderness toward failures that are predictable. Classic office suites with toolbars like crowded shelves. DOS games that insist on monochrome courage. The earliest chatroom interfaces—flat, blinking cursors, nicknames like masks carved from plain text. Visitors come here to touch the past with their fingertips, to hear the click-clack of mechanical keys and the soft fan-rattle that sounds like a tired insect. They come for archaeology. I keep the bones intact.

On one shelf, under a cloth that smells of detergent and sun-dried cotton, I keep a folder labeled in pencil: “CROSSOVER LOOKS.” The paper inside is not paper, not really—it’s printouts, dot-matrix fanfold with perforated edges, the holes like tiny wounds along both sides. I printed them that way on purpose, because fashion is always pretending it’s new, and dot-matrix refuses to pretend. The images are low-resolution and still somehow sharp: One Punch Man’s Saitama, bald and calm as an unplugged lamp, meeting avant-garde streetwear with the kind of indifference that makes it feel dangerous.

Saitama is the purest interface I’ve ever seen. No complicated settings. No hidden menus. One button, one outcome. And that’s exactly why he belongs in clothes that are all seams and interruptions—jackets that look like they were folded wrong on purpose, pants that hang asymmetrically like a sentence that stops mid-thought, sneakers built like small architectural models. In the museum, we call it a “bold crossover,” but boldness isn’t loudness. Boldness is choosing a silhouette that doesn’t apologize.

There is a look I like to start with because it feels like the first time a machine boots after years in a closet: a cocoon coat, matte black, with a diagonal zipper that cuts across the chest like a slash of ink. One sleeve is slightly longer, swallowing the wrist, while the other ends early, exposing the forearm—skin against fabric, the body reminding you it’s real. Under it, a high-neck base layer in bone-white, tight enough to show the tension of a shoulder blade when you move. Saitama’s cape becomes a detachable panel, clipped at the collar like an afterthought—something you can remove, fold, and live without. The pants are wide on one leg, tapered on the other, like two different philosophies forced to share a waistline. When he walks, you can hear the cloth brush itself, a soft shff-shff like pages turning.

Streetwear, at its best, is an argument made with textiles. Avant-garde streetwear is that argument delivered with a stutter, a glitch, a deliberate misalignment. It loves the kind of detail you only notice after staring: exposed bartacks, raw hems that fray like old rope, panels of ripstop stitched onto wool the way you patch a beloved bag because you can’t bear to replace it. Put that on Saitama and you get a paradox that tastes like cold rain: a man who can end anything in one punch wearing garments that look like they’ve survived a hundred small disasters.

In the museum’s back room, I have a rack made from scavenged server rails. I hang my “Saitama set” there when I’m not showing it—because yes, I made a few pieces myself, hand-sewn and imperfect, the way early software shipped. The fabric has that plastic-chemical scent of fresh technical textiles, mixed with the iron smell of my needle after it pricked my finger. I learned to stitch like I learned to debug: slowly, resentfully at first, then with a kind of love for the discipline.

Visitors ask why this offline place cares about fashion. I tell them: because both are about interfaces. A GUI is a promise you can touch. A jacket is a promise you can wear. Both can lie.

When Saitama “meets” avant-garde styling in my museum, it happens in rooms that are already haunted by choices. A classic chatroom screen sits nearby, green text on black, a blinking cursor like a heartbeat refusing to stop. I’ve seen people stand in front of it and suddenly look embarrassed, as if their past selves might walk in and recognize them. Then they turn to the fashion prints and laugh—relief, maybe. The laugh has breath in it. Fashion gives them permission to be playful with identity again, to try on a new outline.

Here’s something most outsiders don’t know: the last time I truly thought the museum would die wasn’t when electricity got expensive, or when the city’s internet went down for three days and everyone panicked like fish in a drained pond. It was when the final local capacitor re-forming shop closed—an old couple with nicotine-yellow fingernails who knew how to coax life back into power supplies that should have been buried. They shut their door without a sign. No announcement. Just gone. That day, I held a dead motherboard like a plate of cold food, staring at it, trying to decide if I was still preserving history or just hoarding rot.

That’s the first private detail: I have a ledger, handwritten, where I record each component that fails beyond repair. Not model numbers—stories. “VGA card died during a child’s first Doom level.” “Floppy drive belt snapped while a couple re-read their old love letters.” I keep those notes because when parts vanish, meaning is all that remains. And meaning, unlike capacitors, can be regenerated if you’re patient.

The second detail is uglier. There is a machine here that has never been shown to visitors: a 486 tower that still boots into a chat client from the early days, complete with a list of handles that nobody alive remembers. The hard drive inside it was not mine originally. It came to me in a plain box, no return address, wrapped in a sweater that smelled of camphor. I spent two nights cloning it sector-by-sector because the bearings screamed like a tiny animal. I could have wiped it. That would have been the “ethical” thing, the clean thing, the thing you can explain in a sentence. Instead I preserved it—because museums preserve, and because I’m not as pure as the rules I recite. On the third night, after the clone succeeded, I did wipe the original. My hands shook. I wrote in the ledger: “Sometimes preservation is just delaying a farewell.” Outsiders come here to feel nostalgia. They don’t see the moral mildew that grows under it.

And the third detail—this is the one that takes time to earn, because you only learn it when you stop romanticizing stubbornness: I keep a box of “last parts,” sealed with red tape. Inside are the final spare CRT flyback transformer I may ever find, a bag of keyboard springs, a handful of IDE ribbon cables that still smell faintly of machine oil. The box is not for maintenance. It is for the end. When the old system truly collapses—when the last parts factory closes, when the last donor machine becomes too brittle to cannibalize—I will not spend those parts trying to keep everything alive. I will choose three exhibits to keep running, the way you choose three photographs when your house is on fire. The rest will become still-life. Their silence will be part of the collection.

That’s what Saitama teaches me, in a way no heroic speech can: power doesn’t save you from selection. It only changes how quickly you can make it.

So I style him like a man who could keep everything, and still doesn’t. A cropped utility vest with too many pockets—pockets like menus, pockets like temptations. A skirt-layer over tapered pants, swishing against the knees like a curtain. Gloves with cut fingers, because touch matters. A hood that sits off-center, casting one eye into shade. In one look, the palette is all industrial ash: graphite, concrete, faded black. In another, it’s surgical: optic white, reflective tape that flares when the flash hits, a single strip of red like an error message you can’t ignore. I imagine the cape replaced by a long scarf in technical knit, snagging slightly on a raw seam, reminding you it’s not a drawing; it’s fabric with friction.

In the museum’s main hall, the soundscape is a choir of small mechanical honesties: fans, relays, the click of a mouse with a stiff scroll wheel. When I wear one of the asymmetrical coats during a guided walk, visitors notice the way it moves before they notice what it “means.” The fabric whispers. The zipper teeth chatter softly. The lining brushes my forearms like cool water. That’s the point. The body is where all this ends up: the nostalgia, the fashion, the stubbornness, the grief. Not in the cloud. Not in an archive. In skin and sweat and the slight ache in your wrist after too many hours repairing something that will fail again.

Late at night, after the last visitor leaves and the door locks with a final, satisfied clunk, I sit at a terminal that can’t go online and I look at Saitama’s face in low-resolution print. It’s blank in the way old software splash screens are blank—confident that the work is elsewhere. I think about the day someone will stand in this museum and ask the bluntest question: Why keep any of this? Why not let it die and make room?

I don’t answer with a thesis. I answer with an action. I dust the keys. I reseat a cable. I fold a cape-panel and clip it back onto a collar. I let a chatroom cursor blink in a room that smells like warm plastic and old paper. I keep the museum offline, not because I’m afraid of the new world, but because I want one place where the past doesn’t get overwritten by convenience.

Saitama, in avant-garde streetwear, is my quiet joke and my quiet prayer: the strongest man in a silhouette made of deliberate flaws, walking through a room of obsolete machines that still hum because someone cared enough to listen. And if the day comes when the last part is gone and the last screen goes dark, I already know what I’ll do.

I’ll leave three exhibits running like candles. I’ll label the silent ones with their stories. And on the museum door, in my own handwriting, I’ll tape a note that doesn’t pretend this is anything but physical:

“Power is off. Memory remains. Please don’t knock.”