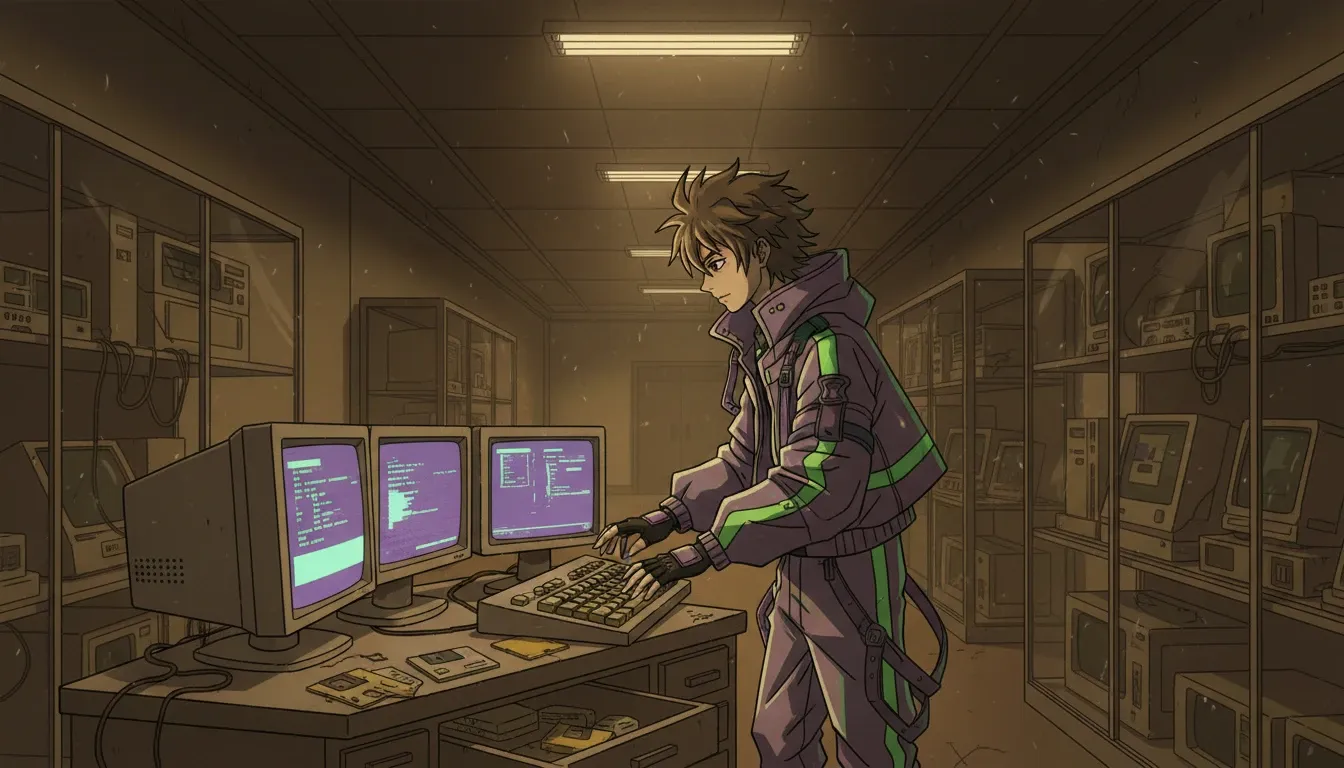

A dimly lit museum hallway, showcasing vintage technology. A young hero in avant-garde streetwear, bold layers with neon textures clashing—lime and violet mesh. He examines a dusty workstation, hands hovering over a vintage keyboard. The air filled with the scent of warmed dust and old manuals. Flickering CRT displays cast soft glows, illuminating the room's mechanical keys. Details of cracked floppy disks and yellowed plastics surround him, creating a nostalgic yet vibrant atmosphere of exploration and curiosity

The museum only boots when the hallway is cold.

I keep it that way on purpose—an old habit from years of coaxing failing capacitors into cooperation. The door sticks, the kind of sticky that smells faintly of oxidized brass and stale rubber. When it finally gives, the room answers with a chorus of tired fans, a dry electric breath, and the soft, guilty click of mechanical keys settling under dust covers. There are no cloud accounts here, no updates, no telemetry. Just an offline sanctuary on machines that still remember when progress had edges.

Visitors come for the fossil layer: the beige towers with yellowed plastic, the sharp blue glow of CRTs, the DOS games that flicker like campfires. They run their fingers along the ridges of old mouse balls like they’re reading braille. They laugh when the first chatrooms appear—blocky, monochrome boxes where strangers used to confess their lives one slow line at a time. I watch them the way a conservator watches a child near a vase: with affection and a quiet readiness to catch what slips.

On the day Deku arrived, the air had the particular smell of warmed dust and printed manuals—paper that has absorbed a decade of summers. He stepped in carefully, like every square foot might be a trap. But he wasn’t timid. He was attentive, the kind of attention that lands on small things: the hairline crack at the corner of a floppy disk label, the way the Enter key on a Model M feels like pressing a miniature door shut.

He didn’t dress like a museum-goer.

Avant-garde streetwear—bold layers, asymmetry that looked accidental until you stood still and realized it had been measured. A jacket cut high on one side, long on the other; straps that didn’t hold anything but still implied function. Under the fluorescents, his neon textures fought each other: lime against violet, a shimmering mesh that caught the light like fish scales. It should have looked like noise. Instead it looked like courage made wearable—like someone had decided that contrast wasn’t a flaw, but a declaration.

He paused by my oldest workstation. The cursor blinked patiently in a black void.

“Is it okay,” he asked, “if I try?”

His voice was soft, but his hands were already hovering with that familiar itch—an instinct to help, to fix, to test the limits gently before pushing them hard. I nodded, and the chair squealed under him, spring metal complaining in an honest way modern furniture has forgotten.

He typed dir like he’d said the word before. When the directory listing appeared, he exhaled through his nose as if smelling something good. Not nostalgia—something stranger. Relief.

Because in my museum, nothing pretends to be seamless. Things wait. Things fail loudly. Things tell you, in plain text, what went wrong.

He wandered between exhibits like someone walking through a wardrobe of borrowed skins. The earliest office suite—menus stacked like paper folders. A first-generation chat interface where emotions had to be spelled out or not at all. A DOS platformer where the jump felt like a little betrayal of gravity.

Then he found my favorite cabinet: the “failed designs” shelf. Prototypes, orphaned ideas, abandoned interfaces. The artifacts that never became history because the market refused to adopt them.

“Why keep these?” he asked, fingers grazing the edge of a box that once promised “The Future of Personal Productivity.”

I could have given the usual sermon about preservation. Instead I told him the truth.

“Because failure leaves fingerprints,” I said. “And you can learn a lot from the pressure points.”

He looked at me—green eyes sharp under the museum’s old light—and said, “That’s what my costume feels like sometimes.”

He said it without self-pity. Just as an observation of weight, of friction. Outside, he’d be called a hero in training, a symbol in the making. Inside this room, he was just a young man in loud fabric that scraped softly when he moved, learning how to hold himself.

I watched him, and I realized something I hadn’t expected: the clash in his outfit wasn’t unlike the clash in my museum. Neon against beige. Future against obsolete. A deliberate refusal to blend.

He stopped at a terminal running a primitive chatroom I’d rebuilt from archived binaries, coaxed back to life through careful emulation. The interface was stark. A list of handles. A text field. No avatars, no algorithm deciding who mattered.

He typed a greeting.

A minute passed.

Nothing.

He frowned the way someone frowns at a silent friend. Then he leaned closer, as if proximity could convince the system to respond.

I reached behind the monitor and tapped the cable with two fingers.

“Bad contact?” he asked.

“Worse,” I said. “A deliberate one.”

That was the first of the museum’s small secrets that outsiders don’t know: the chatroom is wired to a loopback network that never touches the outside world, but it does touch my archive. The “users” are not people. They are logs—transcripts of real conversations from decades ago, scrubbed, anonymized, and replayed on a schedule that matches the original cadence. If you come at the right hour, you can watch an argument unfold exactly as it did in 1999, each line arriving with the same pauses, the same typos, the same sudden silences where someone decided not to hit Enter.

It takes time to learn when those hours are. You have to sit and wait. Most visitors don’t.

Deku did.

He sat back, letting the chair creak, and folded his hands, neon sleeves sliding over each other with a soft hiss. The room hummed. The CRT warmed, its glass faintly radiating heat like a small animal. Dust motes drifted through the beam of the desk lamp.

Finally, a line appeared.

A handle he didn’t recognize.

A simple sentence: you still here?

Deku’s shoulders loosened, just a fraction.

He typed: Yes. I am.

The museum, in its stubborn offline way, offered him something the modern world rarely does: a conversation that cannot be optimized. You can’t scroll past it. You can’t refresh it into something more entertaining. You can only be present while it arrives.

That night, after the last visitor left and the hallway went quiet again, he stayed.

I don’t let just anyone stay. The second secret—another detail that took me months to build and even longer to trust—is a hidden maintenance partition on the oldest machine, a place where I keep the museum’s “ghost tools”: tiny diagnostic utilities, hand-written scripts, and a personal index of patches for software that no longer has official support. I never mention it. It’s not about paranoia; it’s about integrity. If the wrong person touches it, they can “modernize” my exhibits into death.

Deku found it anyway—not by snooping, but by noticing. He noticed the boot delay. The faint mismatch in the checksum I display on a little label under the keyboard. The way I always, always typed one extra command before launching the chatroom.

He didn’t call me out. He simply asked, “Do you have a way to keep these from breaking forever?”

No one asks “forever” unless they’ve been afraid of losing something.

So I showed him.

In the dim light, the maintenance screen looked like a confession: simple text, simple tools, careful steps. Deku leaned in, eyes tracking each line. His jacket’s asymmetry cast uneven shadows across the keys. The scent of his fabric—synthetic, sharp, almost citrus—mixed with the museum’s warm dust and old plastic. It made the room smell like time folding over itself.

He learned fast. Too fast.

And that’s when the museum’s third secret came out, not from me but from a knock on the door that shouldn’t have happened—three precise taps, measured like a metronome.

A man stepped in without waiting for permission. Clean coat. Clean shoes. The smell of cold air and expensive soap. He looked like the kind of investor who believes empathy is a rounding error. I knew him, though he’d never been a “visitor.” He’d been circling my museum for months with polite emails and increasingly impolite offers.

He smiled as if we were old friends.

“Still playing with antiques?” he asked, eyes flicking over Deku’s neon layers like they were a spreadsheet gone wrong. “Charming.”

Deku stood, the chair legs scraping. He didn’t flare up. He didn’t threaten. He just placed himself between the man and the maintenance terminal in a way that was almost unconscious—protective, practiced, bodily.

The investor’s gaze sharpened. “Ah,” he said. “You brought a mascot.”

I felt something ancient in my chest, a tightness I usually only feel when a hard drive starts clicking in a room full of people. I wanted to snap. But I’ve learned that anger in a museum is like water near old paper: it ruins everything it touches.

“You shouldn’t be here,” I said.

He waved a hand. “I’m exactly where I should be. I’m offering to buy this entire collection. Every disk, every workstation, every failure you’ve curated. Not as a warning. As a resource.”

He spoke the last word like it was holy.

“I want it for a training dataset,” he added, and now Deku’s head tilted slightly—the way he does when he’s mapping a problem in his mind. “Ten years of inspiration,” the investor continued. “Your abandoned interfaces are perfect. They’re unfiltered human intention. No modern polish. No compliance committee. I can build a new generation of products from them.”

The room’s hum suddenly felt louder.

My museum has always been offline because the internet would turn it into content. People would scrape it, remix it, sell it back as nostalgia. But this man didn’t want nostalgia. He wanted extraction. He wanted to turn my careful failures into fuel for an engine that would never say thank you.

Deku’s clothes, for the first time, didn’t look loud. They looked like armor—layered, contradictory, bright enough to be seen, strange enough to be underestimated.

He looked at the investor and said, quietly, “If you take something because it’s useful, you still need to honor what it cost.”

The investor laughed. “Cost? These are dead products.”

Deku’s fingers flexed, the mesh catching the light. “They’re not dead,” he said. “They’re evidence.”

I realized then what the museum had done to him in a single evening: it had given him a way to talk about dignity without slogans. A way to defend the fragile without performing.

The investor turned his attention to me again. “Name your price.”

I could have said a number. I could have pretended to be tempted. But my answer tasted like dust and truth.

“I don’t sell the museum,” I said. “I maintain it.”

He frowned, as if I’d spoken in an obsolete file format. “Maintenance doesn’t scale.”

Deku stepped closer—not threatening, just present. “Neither does being human,” he said.

For a moment, the investor looked genuinely confused, as if the sentence had no place in his model of the world.

Then he left, the door sticking behind him, the museum’s air rushing in to heal the cut of cold he’d brought.

When the silence returned, Deku exhaled—a long breath that seemed to come from somewhere deep. His neon layers shifted, fabric whispering, like the museum itself had leaned closer to listen.

“You really built all this alone?” he asked.

“Not alone,” I said, and gestured to the machines, the disks, the manuals with worn spines. “With them.”

He smiled, small and tired and real. “It feels like a place where you’re allowed to be unfinished,” he said.

That sentence, more than any offer, made me understand why he’d come here in avant-garde clash and asymmetry: because he had lived too long under the pressure to resolve into a single clean silhouette. In my museum, nothing is required to be smooth. The seams can show. The colors can fight. The old can keep breathing without apologizing.

Later, when he finally left, the hallway smelled again of cold air and the faint citrus of his jacket. I sat at the chat terminal and watched another line appear from the past—someone asking, you still here?

I typed back, just as Deku had.

Yes. I am.

The cursor blinked. The fans hummed. The museum continued, stubborn and physical, held together by screws, patience, and the quiet conviction that even obsolete things deserve a room where they can still speak.