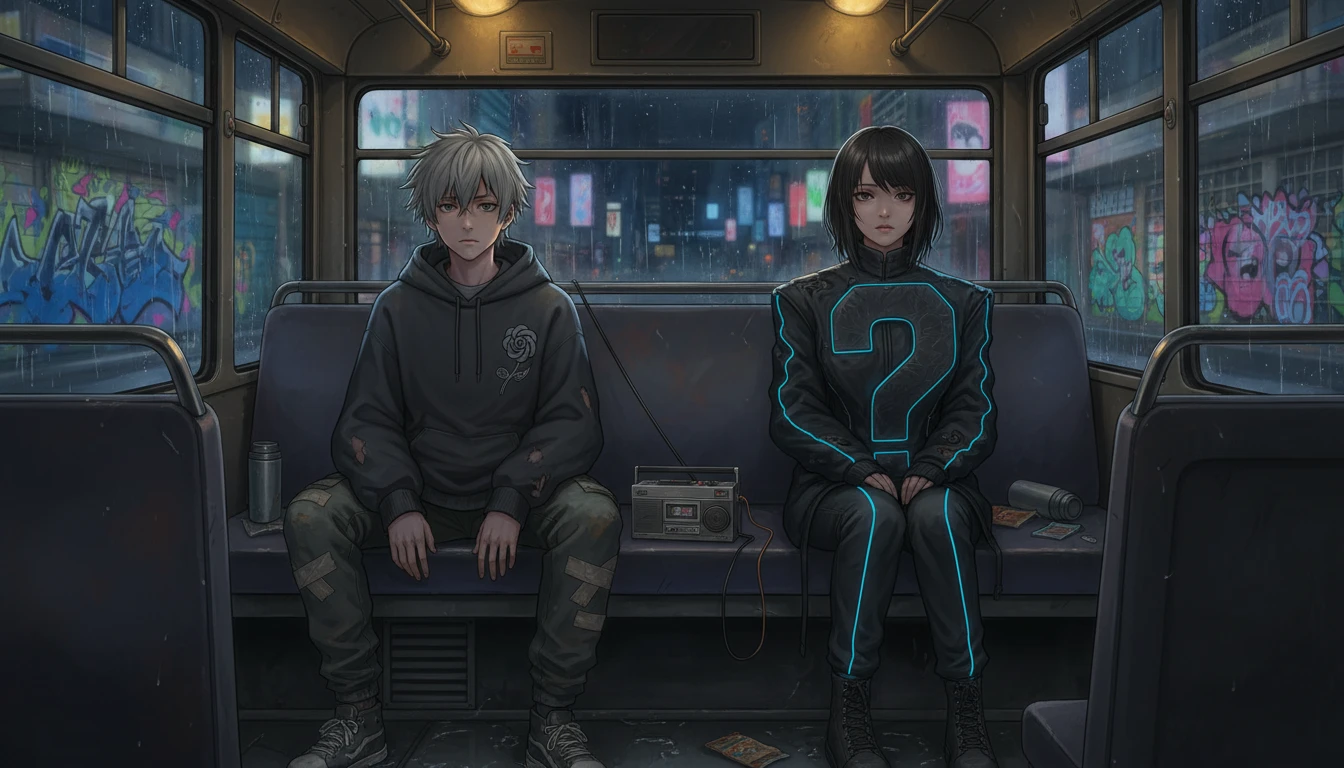

A dimly lit bus interior at midnight, featuring a boy in an ash-colored hoodie with frayed sleeves, a flower stitched on his chest, and a girl in a structured question-mark jacket. The atmosphere is moody with warm yellow cabin lights and a rainy city outside. Details include salt-stained streetwear and translucent tape on cargo pants, capturing the essence of streetwear and avant-garde. The bus is surrounded by urban graffiti, with a cassette recorder on the seat, hinting at untold stories and whispered voices. The scene blends anime character styles with realistic textures and environments

The last bus smells like wet wool and brake dust. It always has. Fifteen years of midnight routes have taught my palms the grain of the steering wheel the way a tailor learns cloth—by friction, by repetition, by the quiet promise that something will snag if you pull too hard. Above my head the cabin light hums, tired and yellow, and the city slides past the windows like a long, half-erased caption.

I drive with one ear on the engine, and the other on people.

In the coin tray, under the printed route map that’s gone soft at the folds, I keep an old cassette recorder. A small thing, scuffed as a street curb. I never point it at anyone. I just let it drink the air—strangers’ talk, the scrape of sneakers on rubber flooring, the cough that tries to pretend it isn’t loneliness, the sudden brave singing that comes when the last bus is also the last audience.

Some nights, when the bus kneels at a stop and exhales its doors open, the outside cold rushes in and makes the inside feel like a held breath. That’s when I hear fashion the clearest. Not the kind you see in glossy shop windows—this is the kind that clings to bodies that have been awake too long. Streetwear at 1:17 a.m. has salt stains. Avant-garde at 2:03 a.m. has safety pins that have already proven their loyalty.

Tonight there’s a boy in a hoodie the color of old ash. The hood is up, but he’s not hiding; he’s just trying to be held by fabric. His sleeves are cut uneven, a deliberate wrongness. The left cuff frays into a soft fringe that brushes his knuckles whenever he adjusts his strap. On his chest, faint as a watermark, a flower is stitched in thread that catches light only when he turns—like a memory that refuses to show itself until you stop chasing it.

Two seats behind him, a girl wears a jacket built like a question mark: one shoulder sharply structured, the other falling loose, as if the garment can’t decide whether it wants to be armor or apology. Her pants are cargo, but the pockets have been sealed shut with translucent tape, the kind you’d use to protect a label in a museum. Her shoes are loud—thick soles, scuffed toes—yet she walks like she doesn’t want to wake the city.

They aren’t cosplaying grief. They’re tailoring it.

I know that feeling. I’ve watched people carry their dead in plastic bags of convenience store snacks and in the careful way they don’t sit in certain seats because “he used to.” I’ve watched them dress like a door they can’t unlock, hoping the right silhouette might make the past click into place.

On the cassette, the tape reels whisper. The recorder catches their voices in soft grain, like the city itself has been powdered and pressed.

“You ever think,” the hoodie boy says, “that streetwear is just a uniform for people who don’t want to be seen as hurt?”

The girl laughs, but it’s thin. “And avant-garde is for people who want to be seen as hurt—but on their own terms.”

At the next stop, the doors open. A gust of rain-scented wind. A man boards who looks like he belongs to a different species of night: clean coat, watch that glints even under tired bulbs, phone held like a compass. He sits upright, knees aligned, hands folded—an investor’s posture, the kind that tries to discipline even the air around it.

His ringtone is a metronome. Efficiency, tapping its foot.

“Sorry,” he says to no one, but loud enough for the bus to forgive him. Then, into the phone: “We can’t monetize nostalgia. We can package it.”

The girl’s head tilts. The hoodie boy’s fingers tighten around his strap. In the window’s reflection, their faces look like layered stickers—street and dream, grit and design, all pasted onto a moving sheet of glass.

I’ve heard the name Menma more times than a driver should. Not screamed. Not advertised. Whispered—like a private password. Anohana. The Flower We Saw That Day. People bring it up when the bus is almost empty and the city has stopped pretending to be brave.

Once, years ago, a group of students sat where the hoodie boy sits now. They passed a single pair of earbuds like it was a communion cup. Every so often, one of them would glance up at the ceiling and blink hard, as if trying to keep a ghost from spilling out. When they left, I found something small wedged between the seat and the wall: a folded paper crane made from a ticket stub. On the inside, written in tight pen strokes, was a line in English that didn’t match the rest of the handwriting: “I’ll be found where we used to laugh.” I kept it in the driver’s compartment until the ink went pale.

That’s one detail nobody outside this route would know: on rainy nights, paper cranes made from last-bus tickets stick to the seat foam as if the bus itself is trying to keep them.

Tonight, the investor hears the word “Menma” drift from the girl’s mouth, and he turns like he’s been pinged by an algorithm.

“Excuse me,” he says. “Did you say… Menma? Like the character? We’re scouting for IP-adjacent collaborations.”

The hoodie boy lets out a breath through his nose—a sound halfway between a laugh and a warning. “IP-adjacent,” he repeats, tasting it like a foreign spice.

The girl’s hands move to her jacket’s asymmetrical seam, worrying the thread. “It’s not a brand,” she says. “It’s a bruise.”

The investor smiles the way people smile when they have never had to sit with someone else’s grief for long. “Bruises are data,” he says. “They tell you where impact happened. We can build product narratives around impact.”

On the cassette, his words sound even colder, sharpened by tape hiss.

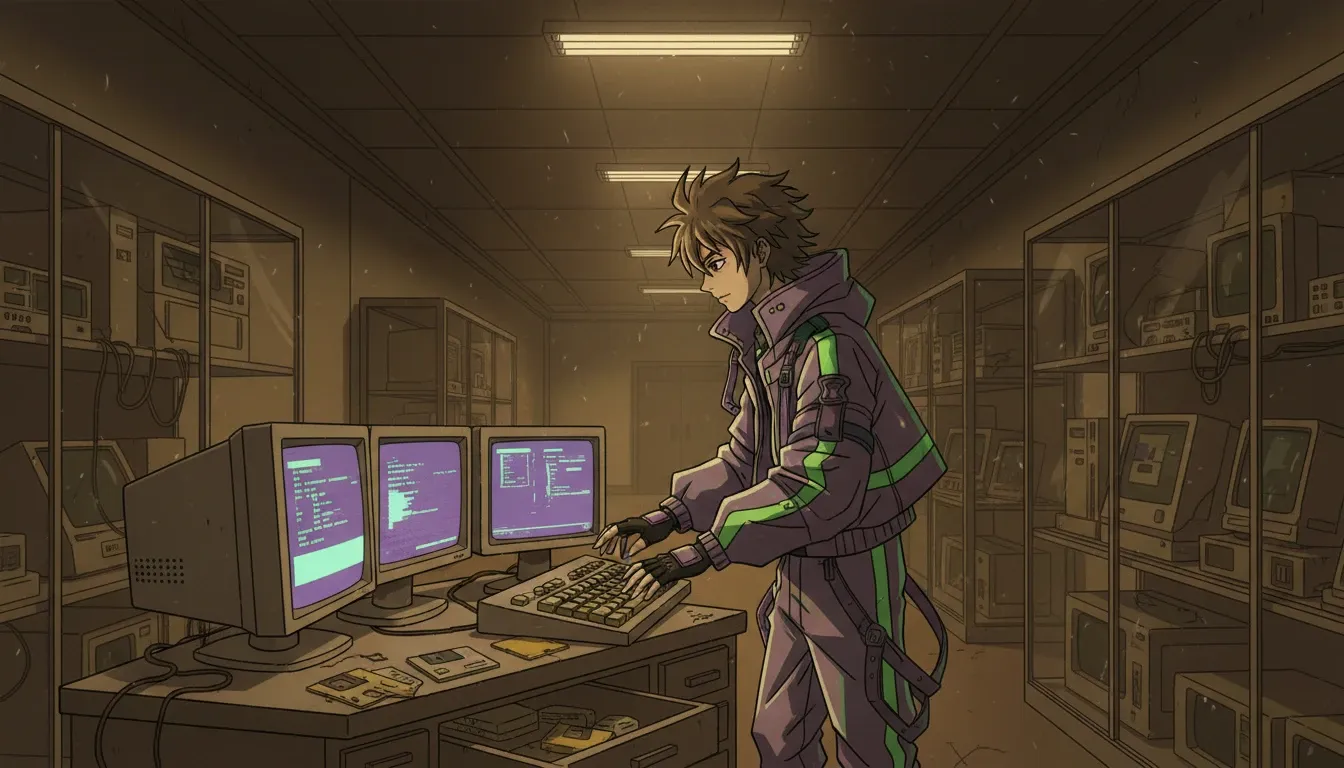

Here’s a second detail, quieter and harder-earned: three years ago, a tech obsessive—one of those people who talk about GPUs like they’re pets—rode my last bus for six months straight. He was building an AI that could “restore voices” from low-quality recordings. He said he could pull a person out of static if you fed the machine enough nights. One evening, he asked me, with hands trembling from too much caffeine, if I had any old tapes.

I lied and said no.

I watched him get off at the river stop, where the water smells like rust and algae, and I wondered what it would mean to resurrect a voice without resurrecting the body that once carried it. That’s the kind of question only a last bus asks.

Now this investor—efficiency polished to a shine—is brushing up against the same edge: the desire to turn absence into something you can hold, sell, share.

The hoodie boy says, “You want to fuse streetwear and avant-garde? Fine. But don’t make it a costume party. Make it a way to walk with what you lost.”

The girl nods. “Streetwear is the street: sweat, concrete, people’s eyes. Avant-garde is the wound you refuse to bandage neatly. The fusion is not aesthetic—it’s permission.”

The investor’s gaze sharpens. He’s not stupid. He’s just trained to translate feeling into numbers. “Permission,” he repeats. “So… community activation.”

The hoodie boy leans forward, elbows on knees. “No. Not activation. A vigil.”

Outside, the city’s neon bleeds into puddles. Inside, someone in the back starts humming—a soft, unsteady melody, as if they’re testing whether the air will let it live. The bus’s heater clicks on, pushing warm breath along the floor. It smells like dust waking up.

The girl reaches into her bag and pulls out a strip of fabric, folded like a secret. She unfolds it slowly. It’s a sash, but not ceremonial—more like a bandage. On it is a tiny embroidered flower, almost hidden, stitched with thread that changes color when it catches light. She drapes it across her jacket’s severe shoulder, letting it fall diagonally, imperfect, alive.

“Menma isn’t symmetrical,” she says. “Grief isn’t. That’s why the cut has to break rules.”

The investor watches the sash like he’s seeing a market he didn’t know existed: not customers, but mourners. “If I funded something,” he says carefully, “what would it look like? What’s the deliverable?”

The hoodie boy thinks. The bus sways through a turn, and the recorder bumps gently against the coin tray—like a heart remembering to beat.

“It would look like this,” he says. “A hoodie that has one sleeve longer, because you keep reaching for someone who isn’t there. A jacket with a pocket you can’t open, because there are things you can’t fix by retrieving them. Cargo pockets sealed shut, because carrying isn’t always the same as keeping.”

“And,” the girl adds, “a label you can’t scan. No QR codes. No cloud. Just a stitched name on the inside, the kind that touches skin. So it’s yours in the way pain is yours.”

The investor flinches, almost imperceptibly. Maybe he has his own sealed pocket. People like him do, even if they call it “work-life balance.”

The humming in the back grows into a song—thin but earnest, a voice catching on certain notes like fingers catching on torn fabric. Someone else joins in, quietly, and the harmony is messy, human. The bus becomes a moving room of imperfect sound, the kind no studio would approve.

Here’s the third detail, the one that takes time to learn because you have to live in the gaps between stops: on my route there’s a stretch of road where the city’s cell towers dip, just for forty seconds. Every phone loses signal. Every notification dies. People look up, as if surprised to find their own thoughts sitting beside them. In that small dead zone, I’ve heard more apologies than in any church.

We enter it now. The investor’s phone goes quiet. The screen shows No Service. His thumb hovers, lost.

The hoodie boy looks out the window, and for a second his reflection overlaps a streetlight, making the flower on his chest flash like a signal. The girl closes her eyes, letting the song wash over her like warm rain. The investor, stripped of his metronome, listens.

In that signal-less pocket of the city, the fusion becomes what it always should have been: not trend, but testimony. Streetwear brings the body—sweat, bruises, the blunt honesty of asphalt. Avant-garde brings the refusal to make suffering pretty for consumption. Together they make garments that admit the truth: that we dress not only to be seen, but to survive being seen.

The bus rolls on. The dead zone ends. Phones wake up. The investor’s screen floods with numbers again, but he doesn’t look right away. Instead he says, softer, “What if we built it as a limited run with no restock. Not scarcity marketing—just… honoring that some days don’t come back.”

The hoodie boy doesn’t answer immediately. He listens to the song. He listens to the bus’s joints creak. He listens to the city’s long exhale.

Then he says, “A vigil doesn’t need an audience. But if you’re going to help, don’t turn the flower into a logo. Keep it small. Keep it close. Like it’s stitched for the person wearing it, not for strangers’ eyes.”

At the terminal stop, the last of the night, the passengers file out with that peculiar tenderness people have when they’ve shared a room of darkness. The girl pauses by the front, her jacket’s sharp shoulder catching the light.

“Driver,” she says, as if she’s known me longer than ten stops, “do you ever replay them? The tapes.”

I keep my hands on the wheel. My fingers smell faintly of metal and old vinyl. “Sometimes,” I say. “When the city feels too clean in the morning. I play them to remember the truth has fingerprints.”

She nods, and for a moment the embroidered flower on her sash seems to breathe.

They step into the wet street. The doors close. The bus becomes my private vessel again.

I turn off the recorder. The cassette clicks, a tiny coffin shutting.

And in the quiet that follows—the quiet that always feels like a page turning—I can still hear the night’s fusion: the street’s grit against the avant-garde’s broken symmetry, stitched together by the stubborn human need to carry loss without letting it become merchandise.

The city’s most real stories are not built in studios or boardrooms. They happen here, in a moving cabin under tired lights, where strangers lend each other their voices for a few stops, and where a small flower—kept deliberately small—can survive the pressure of being remembered.