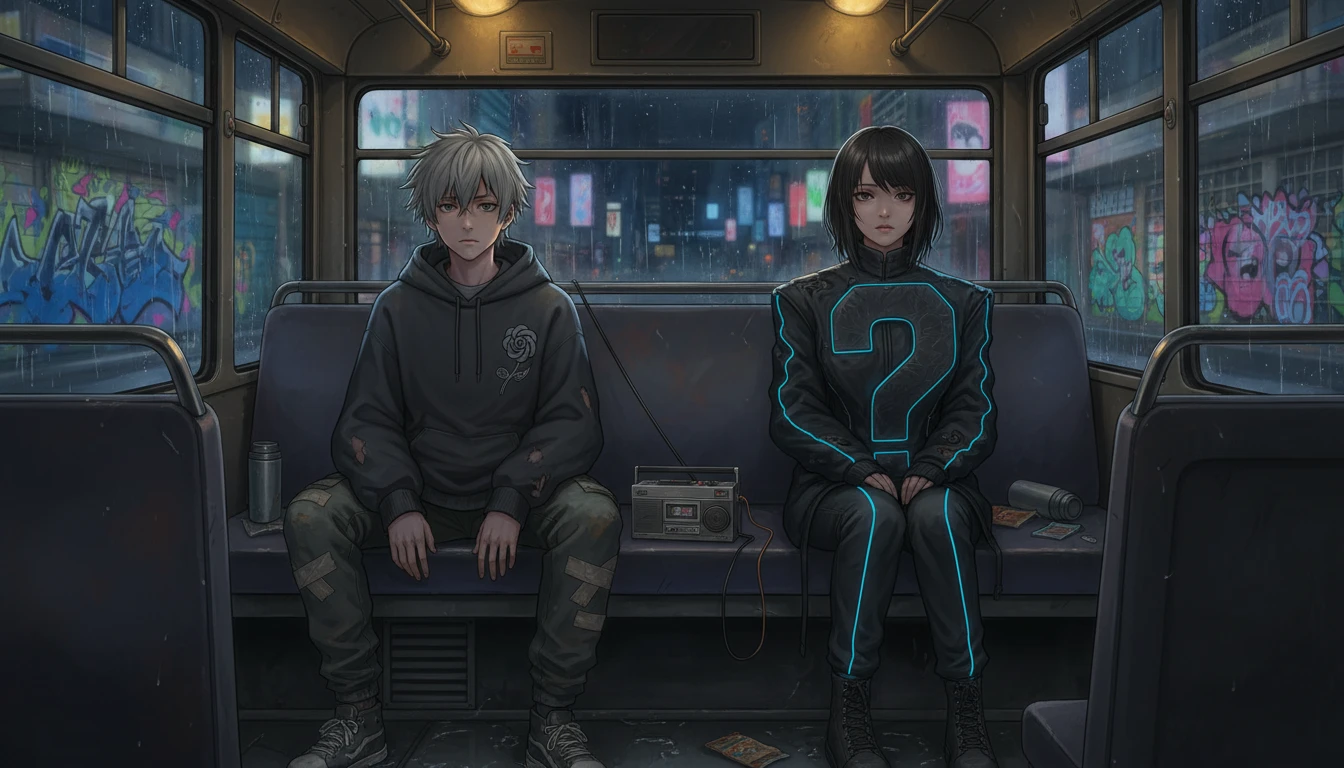

Ken Kaneki sits on a dimly lit bus at 1:27 a.m., enveloped in shadows and city lights, his ash-colored hair contrasting with the bold layered streetwear of three laughing kids across the aisle. The scene captures the ambiance of a moving confession booth, with metallic textures and illuminated hues of gold and shadow. Ken's piercing gaze reflects hunger amidst the vibrant fashion armor of oversized blazers, pleated skirts, and asymmetric coats, against the backdrop of shuttered workshops. The atmosphere is thick with the scent of nocturnal urban life, layering emotions like the fashionable garments worn

The last bus is not a route so much as it is a moving confession booth—metal ribs, rubber floor, windows filmed with city breath. I have driven it for fifteen years, the same late loop that skims the river, cuts through office districts after they’ve gone hollow, and threads the sleeping neighborhoods where even dogs stop arguing with the dark. Under my seat, wrapped in a faded microfiber cloth that once belonged to my daughter’s school uniform, I keep an old cassette recorder. The kind with a stubborn mechanical click, a belly that warms in your palm, and a cheap red light that blinks like a guilty eye.

I don’t record for evidence. I record because the city tells the truth only when it thinks no one is listening.

At 1:27 a.m., the bus smells like wet wool, nicotine trapped in cuffs, fried garlic leaking from a paper bag, and that thin medicinal scent that clings to people who spend too much time under fluorescent lights. The engine hums in my bones; the steering wheel is cold enough to numb the pads of my fingers. Every stop is a soft impact—air brakes sighing, doors yawning open, night air rushing in like black water.

Tonight a boy gets on at the underpass with the vending machines. He moves like he’s trying not to be seen, shoulders angled, hood pulled too far forward. He sits halfway down, alone. His hair is the wrong white for dye—more like ash left after a fire decides it’s done being beautiful. When he lifts his head, I see one eye catch the light wrong: not glassy, not sick, just… hungry in a way you can’t name without sounding cruel.

Ken Kaneki, I think. Not because people announce their names on the last bus. Because stories arrive dressed as strangers, and this one has Tokyo Ghoul written in the space between his breaths.

Across the aisle, a trio of kids in bold layered streetwear are laughing like they’ve stolen something and got away with it: oversized blazer over a cropped hoodie, pleated skirt over track pants, a scarf stitched from two different fabrics so the seam is deliberately visible. Their fits are loud in the way a bruised heart can be loud—defiant, designed. One of them wears a long asymmetric coat that drapes longer on the left, swinging like a pendulum when she talks. Another has a vest strapped with utility buckles, the kind you’d expect to be functional, except every pocket is too shallow to hold anything real. Fashion as armor, fashion as theater, fashion as a dare.

They’re doing what young people do: turning fear into style before fear can turn them into something else.

I flick the recorder on. The click is soft, but in the quiet it feels like a taboo.

The bus passes a row of shuttered workshops, and the streetlights paint everyone in alternating stripes—gold, then shadow, then gold again. Layering looks different under those lights. A collar becomes a cliff. A chain becomes a line of tiny moons. The city is an editing software that only knows contrast.

Kaneki watches the trio without meaning to. His gaze sticks for half a second on the asymmetric coat. On the stacked silhouettes. On the deliberate mess of fabrics and straps. Like he recognizes something: the logic of survival, stitched into an outfit. The idea that you can build a new body out of pieces when your old body stops obeying.

One of the kids—thin fingers, nails painted a chipped black—leans forward and says to the others, “If you had to dress like your hunger, what would you wear?”

The others laugh, but the question lands heavy. On the last bus, even jokes have teeth.

Kaneki doesn’t speak. He presses his palm against his thigh as if to hold himself down. The movement is small, but I’ve seen that gesture before in people trying not to explode. In people who are balancing on the thin wire between polite and feral.

The trio begins to talk about styling like it’s religion: how to stack textures without looking like you’re drowning, how to let a graphic tee peek through a blazer like a secret, how to use a harness not as kink but as punctuation. They speak in the language of silhouettes and seams, but underneath it is the same ancient argument: Who are you allowed to be when the world tells you you’re wrong?

Kaneki’s breathing changes when they mention masks.

“Not Halloween masks,” the girl in the asymmetric coat says. “Like, real masks. Something that makes you feel… safe.”

I should not know this, but after fifteen years of nights, I have learned the city has an underground for everything. There’s a tiny place behind an unmarked vending machine near Uguisudani where a man used to sell scrap leather and odd metal bits—buckles that never matched, zippers from discontinued runs. If you came after midnight and didn’t ask too many questions, he’d trade you parts that could become anything: a belt, a restraint, a makeshift strap to keep your layers from slipping apart. Two months ago, that man disappeared. Not arrested. Not dead, as far as I can tell. Just gone, like a removed file. People said the last parts factory in Saitama finally closed, and the supply chain for small hardware collapsed with it. It sounds too boring to matter until you realize: when a city can’t make the little things anymore, the big things start falling apart too. When the old system dies, the new one doesn’t arrive with a ribbon-cutting; it arrives with shortages, improvisation, and quiet panic.

The trio doesn’t know that detail. Outsiders wouldn’t. But I’ve heard the whispers at 2:40 a.m. from men who smell like machine oil and grief.

Kaneki shifts, and his sleeve rides up. There are faint marks—thin lines on the wrist, like someone once tested how tight a strap could go. It could be nothing. It could be everything. The last bus is where “maybe” lives.

They start talking about Tokyo Ghoul without saying the title. About being half-something, about hunger that feels like shame, about the violence of having to pass as normal. The boy with the utility vest says, “I think the hardest part is when people look at you and only see the monster you’re trying not to be.”

Kaneki’s hands clench. His knuckles go pale. He keeps looking out the window as if the city is safer than their words.

The recorder captures a different sound then: a low, shaky hum. Someone at the very back—an old man with a plastic grocery bag—begins to sing under his breath. A song from before my time, melody bent by age but still stubborn. The kind of song you sing when you’ve outlived the reasons to sing. The bus becomes a throat, carrying the note forward, vibrating it through metal and glass.

I remember another night, years ago, when a woman got on with a hardhat in her lap and hands that wouldn’t stop trembling. She told a stranger, “They’re closing the depot. The last one. No more night shifts. No more parts. No more repairs.” She said it like a funeral announcement. Later, she asked the stranger, almost pleading, “If the thing that kept you alive is gone, what do you do?”

That stranger—young, too clean to have answers—said something stupid about starting over.

The woman laughed once, sharp as a snapped thread. “Starting over costs money,” she said. “Starting over costs a face.”

Tonight, watching Kaneki and the kids in their layered defiance, I hear that laugh again, like it’s stitched into the upholstery.

The trio starts arguing about authenticity. “Is it real if you curate it?” one asks. “If you build a persona from clothes, are you lying?”

The girl with the asymmetric coat touches the seam where two fabrics meet, thumb rubbing the join like she’s checking for weakness. “If the world won’t let you live as one thing,” she says, “you learn to layer. You learn to be multiple on purpose.”

Kaneki finally speaks. His voice is quiet, almost swallowed by the engine, but the recorder catches it.

“Layering,” he says, “is how you hide the wounds.”

No one laughs. The bus hits a pothole, and everyone sways together, a brief, involuntary choreography. For a second we’re all the same body: strangers stitched into one moving container.

The boy with chipped black nails leans toward Kaneki. “Do you ever feel like you’re wearing someone else’s life?” he asks, not mocking, not pitying—just asking, like the question itself is a hand offered in the dark.

Kaneki’s jaw tightens. His throat bobs. “I used to think,” he says, “if I could be good enough, careful enough, then I wouldn’t have to hurt anyone. But hunger doesn’t care about morals.”

His words carry a wet edge, like he’s speaking with blood under his tongue.

The bus smells suddenly sharper—cold air rushing in at the next stop, exhaust threading through the door gap, someone’s citrus hand sanitizer cutting through everything. My eyes sting. Maybe it’s the fumes. Maybe it’s the truth.

Outsiders think the city’s secret life happens in clubs, in neon, in the headlines. They don’t know about the quiet collapse—the way a parts supplier shutting down can erase a whole ecosystem of night workers, the way a single policy change can make a decade of expertise feel like trash. They don’t know the feeling of being told, in the most direct way, that what you’ve been loyal to is obsolete.

Two weeks ago, my own depot supervisor handed me a memo with a too-clean font: “Fleet modernization initiative.” Translation: the new buses don’t need people like me. They say the automation will handle night routes. They say cameras will monitor the cabin, algorithms will predict “incidents.” They say it like it’s progress, like my hands on the wheel are an inefficiency to be deleted.

That night I sat in the driver’s seat long after my shift, listening to the engine tick as it cooled, and I asked myself the same question that woman asked years ago: If the thing that kept you alive is gone, what do you do?

I didn’t tell anyone my answer. But I bought fresh batteries for the recorder.

Because when the old system collapses—when the last factory closes, when the depot replaces flesh with software, when the city decides you’re unnecessary—some people disappear. Some people burn. Some people reinvent themselves in the only way they know: by taking scraps and making a new silhouette. A new story. A new kind of hunger.

Kaneki watches the trio adjust their layers—hood under blazer, harness over knit, scarf knotted wrong on purpose. Boldness as camouflage. Avant-garde as survival tactic. Asymmetry as a refusal to look “correct.” In his face I see something like recognition, and something like grief.

The old man in the back stops singing. Silence rushes in to fill the gap, thick and heavy. The city outside is a ribbon of wet asphalt and distant signs, each one blinking like a heartbeat that isn’t sure it wants to continue.

At the next stop, the trio gets off, still laughing, but softer now, as if they’ve realized laughter can be a fragile fabric. The girl in the asymmetric coat glances back once, and for a moment her eyes meet mine in the mirror. I feel caught, not guilty exactly—more like exposed. Like she knows the bus remembers.

Kaneki remains seated. He looks at the empty space they left behind. Then he reaches up and touches the edge of his hood, pulling it forward a little more. A small adjustment. A tiny act of styling. A decision to keep the mask in place for one more stop.

When he finally stands to get off, he moves carefully, like he’s carrying something breakable inside his ribs. At the door, he hesitates. He doesn’t look at me directly, but his voice reaches the front anyway.

“Thank you,” he says, to no one in particular, to the bus, to the night, to the fact that for a few minutes he wasn’t alone in his hunger.

The doors close. The bus exhales. I drive on.

Under my seat, the recorder’s tape turns, quietly gathering sighs, fragments, the aftertaste of song. I tell myself it’s for the city. I tell myself it’s for history. But if I’m honest, it’s for the same reason those kids layer fabric until they look like a moving collage, and for the same reason Kaneki pulls his hood down like a curtain:

Because when everything else is taken—when the old system dies, when your meaning is questioned with a single memo or a single stare—you still get to choose how you move through the dark.

And on the last bus, in the belly of this sleepless city, that choice is the most avant-garde thing of all.