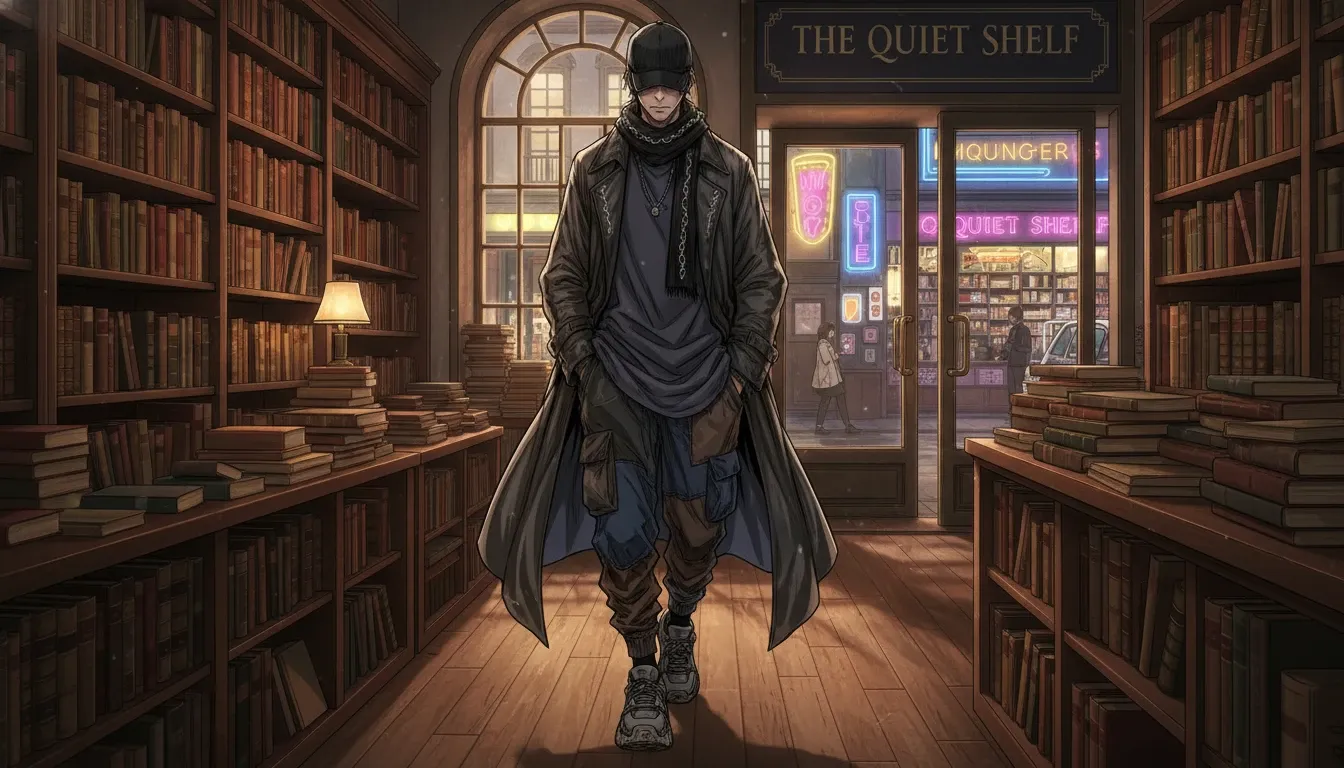

A vibrant streetwear-inspired Gon Freecss stands confidently at a bustling dock, layered in textured fabrics reflecting the energy of the Yangtze River. The scene captures metal and wood, with cranes blinking like tired stars overhead. Surrounding him are scattered porcelain shards, each reflecting a story of survival. The atmosphere is smoky and gritty, illuminated by the warm glow of sunset, creating a contrast between traditional craftsmanship and radical modernity, embodying an honest, raw aesthetic in every detail

The dock never really sleeps. It just changes its noise. Morning is metal on metal, chains coughing up river water. Noon is diesel and wet wood. At night the Yangtze turns black as ink and the cranes blink like slow, tired stars. My studio sits right on the seam between land and hull, close enough that the river smell lives in my clothes, close enough that a careless gust can throw grit onto a fresh join line.

A kid from the tug crew leaned in once and asked, half-joking, “So you’re a doctor for broken bowls?”

I said yes, and then immediately regretted how clean that sounded—because nothing about what I do is clean, not really.

I mend porcelain that has already died once.

Not the polite kind of porcelain you see behind glass. I mean bowls that lived on moving decks, cups that took knuckle hits when a wave slapped the planks, jars that sweated brine and rice wine in the dark belly of a ship. When we dredge a wreck, the shards arrive like teeth in a bucket. I lay them out on felt, wipe them with warm water, and listen with my fingertips. You learn to read breaks the way sailors read clouds.

And then, because I’m alone here and the river gives you too much time, I dress those ghosts in streetwear.

Not literally. Don’t call the museum. I mean I let a certain energy leak into my hands, the kind I get when I rewatch Hunter x Hunter and Gon Freecss shows up with that bright, stubborn body language, all forward motion and no apology. I’ve repaired Ming and Qing ware for collectors who want “invisible” seams, but the river doesn’t do invisible. It does survival. It does scars. So my repairs lately have been loud in a quiet way, like a casual layer that hides a blade of intention.

And—this is where I have to admit something that doesn’t fit the elegant version of the story—sometimes it’s not philosophy at all. Sometimes it’s just me being tired of lying with perfect hands. Sometimes I miss a line by a hair and decide not to fight it. I tell myself it’s “attitude,” but maybe it’s just honesty finally getting impatient.

Dockside Wardrobe, River-Weight Layers

A good streetwear fit starts with weight. So does a good repair.

When I grind a fill to match the curve of a rim, I can feel the bowl’s old center of gravity. That’s how I decide whether it was for soup or for rinsing hands, whether it sat on a galley shelf or traveled wrapped in straw under a bunk. A wide, shallow dish with worn foot rings tells me it got dragged often, used fast, wiped without ceremony. That’s not a scholar’s desk. That’s a working deck.

So I build my “Gon” in layers. Base layer is function, the original purpose of the object. Mid layer is the route, the logistics of how it moved. Top layer is attitude, the radical runway energy I let into the seam: a line that does not pretend to be ancient, but insists on being honest—

—and I’m going to pause there, because “honest” is one of those words that behaves like a halo until you actually have to wear it.

My hands smell like epoxy and river mud. The heat gun makes the air taste faintly sweet and chemical, like burnt sugar that shouldn’t be eaten. When the resin cures, it gives off a warmth that feels like a small animal breathing under my palm. That physicality is why I can’t talk about fashion like it’s abstract. A fit is a temperature. A repair is a temperature. Gon’s outfits, simple as they look, always read to me like gear: ready to sprint, ready to bleed, ready to improvise.

I drifted for a second just now—thinking about last night’s refrigerator, that low-frequency hum that made it hard to sleep. I kept wondering if something tiny was stuck behind the panel, some dust clump rubbing a fan blade. A microscopic problem, a whole night ruined. It’s ridiculous how often life is that: not tragedy, not drama, just a small unnamed obstruction. Anyway. Back to the bowl.

The Asymmetry I Trust

I don’t like symmetry. Symmetry is for people who never had to salvage.

On paper, a bowl is a circle. In the river, it becomes a map of stress. One side chips more because it was always stacked left. One handle wears smooth because a right-handed cook grabbed it without thinking. That asymmetry is more informative than any stamp.

I have a shallow celadon fragment on my bench right now, with a glaze crawl on the underside that only forms when the kiln atmosphere shifts late in the firing, a little oxygen sneaking in like gossip. Most people call it a flaw. I call it a timestamp. It tells me that workshop was pushing output, running hotter, taking risks, probably because demand upriver spiked. When I reconstruct the missing rim, I don’t correct the wobble. I echo it, the way a good oversized jacket echoes the slouch of the wearer instead of forcing posture.

And if you want my personal bias, here it is: I think the cleanest “luxury” restorations are sometimes lies told with perfect grammar. The river taught me to speak with a stutter that means something.

Gon Freecss as a Dockside Pattern

People ask why Gon, why anime, why this bright kid in green shorts when my world is mud brown and porcelain white.

Because Gon moves like an object that refuses to be only its category.

He’s “casual” until he’s not. He’s “simple” until he detonates. That switch is exactly how a shard behaves in my hand. A scrap of blue-and-white can look like nothing, and then under angled light you catch a hairline that aligns with another piece, and suddenly you’re holding a whole dinner scene.

Gon’s streetwear odyssey, in my head, is not about logos or hype. It’s about the discipline of layering without losing agility. On deck, sailors dressed the same way. Thin underlayers that dry fast. A heavier outer layer for spray and night wind. A scarf that becomes a bandage. Clothing as a toolkit. Gon would understand that without being told.

And when I build a repair line that stays visible, that’s my runway move. Not shiny. Not screaming. Just a seam that says: this survived, and I am not ashamed of the surgery.

A Cold Detail You Don’t Get From Books

Here’s something outsiders don’t know unless they’ve waited in the mud with us.

There is a point in late autumn when the river drops and exposes a strip of bank that looks like normal clay. It is not normal. It’s a layer of crushed cargo, ground over decades by propellers and flood silt. We call it the “porcelain sand.” If you rub it between your fingers, it sparkles faintly, and it will slice your skin open if you press too hard. That sand gets into everything. It lives in my door track. It lives in my tea.

I should audit myself here: “porcelain sand” isn’t a textbook term, not some formally categorized sediment you can neatly cite. It’s dock language, a rough name for a real thing—pulverized ceramic mixed with silt and grit—that behaves exactly like it sounds. Maybe that matters. Maybe I trust it more because nobody polished the phrase for export.

When I say I repair wreck porcelain, I also mean the wreck repairs me back, carving a habit of caution into my fingertips. That’s streetwear too, in a way: the body learning its city, dressing for it.

When Systems Collapse, What I Keep

Two years ago the last local supplier who made the tiny silicone plugs I use for internal supports shut down. Not a big story. No headline. Just a metal gate rolled down and a phone number that stopped connecting. For a month I tried substitutes from across the country. Wrong density, wrong memory. They either bruised the glaze from the inside or failed under clamp pressure.

This is the part where the old system dies quietly, and you find out whether your craft was real or just convenient.

I made my own plugs by casting from a child’s orthopedic silicone sheet I found at a medical surplus stall. It took me twelve failed pours to get the rebound right. My hands stank like vinegar from the catalyst. I ruined a whole evening of shards because the silicone held a faint oil that refused to wash out and kept my adhesive from biting. I still remember that sick moment when a join line slid a millimeter after I thought it had set, like a promise breaking.

What did I choose? I chose to keep working, but I changed what “success” meant. I stopped chasing invisibility. I began letting repairs show their engineering. A visible seam is easier to inspect, easier to maintain. It’s more honest in a world where parts factories vanish overnight…

…and maybe it’s also me giving future hands a chance. I like to imagine someone else, years from now, holding one of my pieces and understanding where the stress points are because I didn’t hide them. I like to imagine I’m not the last person in this chain.

Say what you want about runway theatrics, but radical energy is often just transparency with confidence.

Another Quiet, Earned Detail

There is a specific smell that tells me a shard came from a galley rather than cargo storage. It’s not fish, not smoke. It’s a thin, stale sweetness trapped in micro-cracks, the residue of fermented grain water that seeped into the body and sat there for centuries. You only notice it when the shard warms under your lamp. If you’ve never had your face inches from wet porcelain at 2 a.m., you’ll miss it entirely.

This one I can’t “prove” in a way a lab would respect, not with what I have here. It’s apprenticeship knowledge, nose-and-lamp knowledge, the kind you trust because it keeps being right. Still—sometimes I worry I’m romanticizing what’s basically contamination. Then I smell it again and my brain insists: galley.

When I catch that smell, I picture hands eating fast, bowls clinking, the deck tilting. Not romance. Just appetite and fatigue. That’s the life that made the object, and it’s the life I try to honor.

Runway on a Workbench

I don’t own a runway. I own a bench scarred with knife marks and adhesive blooms. My “models” are reconstructed bowls that will never be truly whole again. But when I line them up after a week’s work, the way the seams catch the light feels like a procession.

Casual layers meet radical runway energy in the smallest choices.

A matte fill instead of glossy, so the patch reads as fabric not skin. A join line tinted slightly warmer, like a jacket thrown over bare arms. An intentional offset in pattern alignment, echoing the way streetwear breaks rules on purpose. I do this without announcing it, because the river hates announcements. The river respects continuity.

Say, Off Topic

Sometimes, when the cranes stop and the dock goes quiet, I put on a clean shirt and walk to the edge of the water with a repaired cup in my bag. I don’t show it to anyone. I just hold it near the current and let the damp air settle on it. I like that moment when the porcelain cools, when the object remembers what it came from.

Then I go back inside and scrub my hands until the glue smell fades, and I think about Gon again, about that relentless forward lean, the way he treats every setback like a new terrain.

The Identity I Freeze Into Each Piece

Every repaired object in my studio becomes a credential, a passport stamped by breakage.

Not just “this was made in a certain kiln,” but “this moved, this fed people, this survived a sinking, this was found, this was reassembled by someone who refuses to pretend the past was seamless.” That is shipping history with a pulse still in it.

If you handed me a pristine cup from a shop today and asked me to love it, I could. But I would love it like a poster. When you hand me a rim fragment lifted from the Yangtze, sharp as a fingernail, still carrying river grit in its pores, I love it like a scar I earned.

That’s my streetwear odyssey. Not a trend cycle. A dockside practice of layering purpose, route, and attitude until an object can walk again, wearing its repaired seams the way Gon wears his simplicity: casually, dangerously, alive—

—and if the river ever takes it back, if one day another flood or another careless hand undoes my work, I think I’ll still want the seam to be visible in the breaking. Like a last line of handwriting you can’t quite decipher, but you know it meant someone was here.