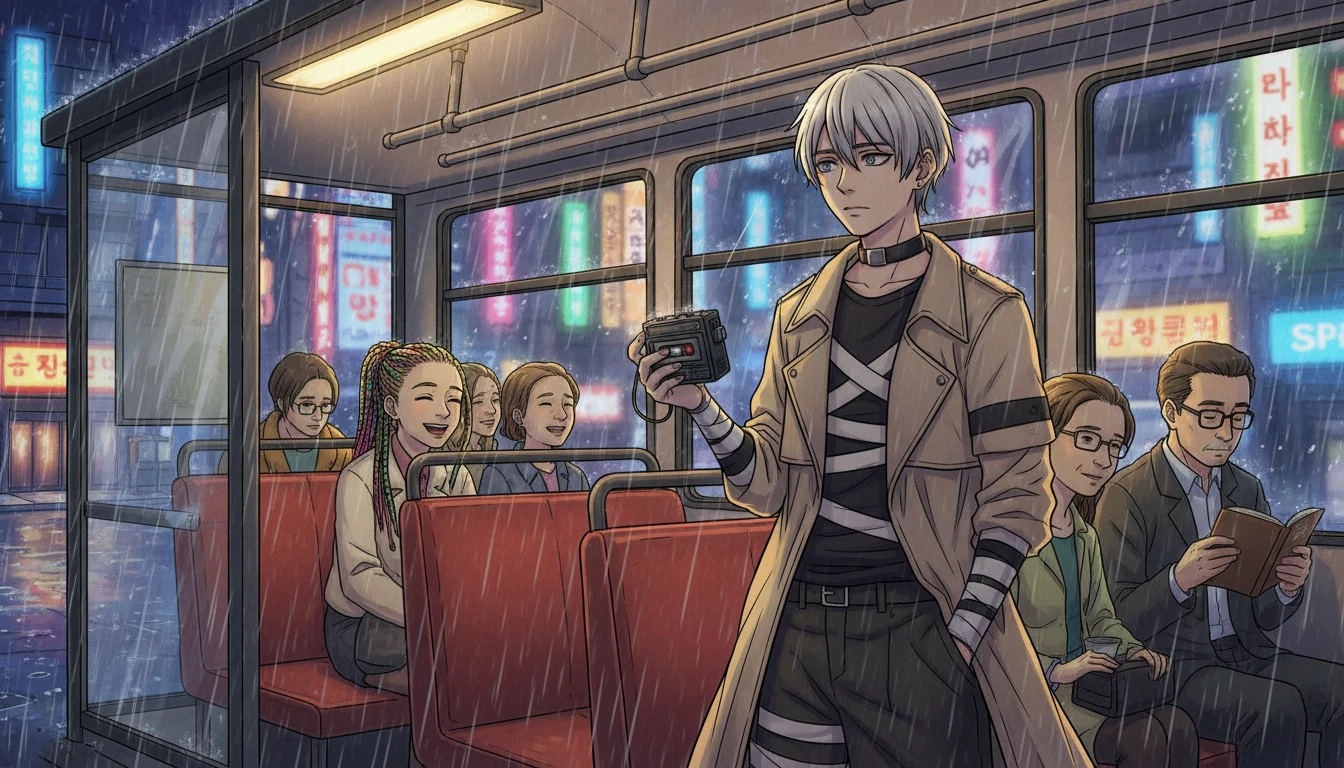

A rainy city night, a bus stop glowing with soft streetlight. Inside the bus, diverse passengers—one in avant-garde layered streetwear inspired by Dazai Osamu, a trench coat draped casually, bandage motifs, silver hair, and expressive eyes. Hum of whispered conversations, laughter, and echoes of life. Rain-slicked streets reflecting neon signs, warm vinyl bus seats, and a hidden cassette recorder capturing the moment. An atmosphere of urban melancholy, vibrant colors contrasting with the dark, capturing the essence of city sounds and fashion as a silent conversation

At 01:47 the city is a wet coin, turned over and over in the palm of my route.

The last bus sighs when it kneels to the curb. Its joints complain in a language older than the LED sign above my head. I have driven this midnight spine for fifteen years—same stops, different faces, the same hunger in everyone’s eyes when the day finally loosens its grip. I keep my hands at ten and two, not from caution but from habit: the wheel’s vinyl is polished smooth where my thumbs live, warmed by hours of contact like a prayer rubbed into existence.

I don’t tell passengers I record them. I don’t post it. I don’t “collect content.” I am not a curator. I am a driver with an old cassette recorder hidden under the fare box, a small rectangle of bruised plastic that smells faintly of iron and old tobacco. Its red light has been covered with a scrap of electrical tape so it won’t betray me. The tape itself came from a roll my father used to wrap wires in winter—its adhesive has the sour-sweet sting of pine resin when you peel it back.

People talk when they think no one listens. They talk the way steam escapes a cracked kettle.

Tonight, someone in the back hums a tune with no chorus, just a line that keeps walking in circles. Another person answers with laughter that has a rough edge, like denim rubbing against a fresh sunburn. A couple argue softly in a dialect I can’t place; their words click like chopsticks in a porcelain bowl. A tired man coughs into his sleeve, and I can hear the cough echo through the bus’s hollow bones.

Somewhere between Stop 11 and Stop 12—where the streetlights thin and the river begins to smell like cold metal—I catch my own reflection in the windshield: uniform collar, silver hair at the temples, eyes that have learned to watch without being seen. I call myself, in my head, a catcher of city sounds. Not the loud ones everyone already knows—the sirens, the karaoke bars, the drunk chants. I mean the tiny truths: the way a zipper stutters when someone’s fingers shake, the soft crack of a knuckle before an apology, the first inhale before a song.

That’s where Dazai shows up.

Not the author alone, not the anime alone—Dazai Osamu as a silhouette that keeps slipping through culture, trading coats the way the city trades seasons. On my bus, I’ve seen him worn like a mood: the trench-coat drape, the bandage motif, the languid slouch that says, I’m present, but I’m not staying. In Bungo Stray Dogs, that image gets sharpened into something street-ready—clean lines, sharp contrasts, irony on the tongue. And out on sidewalks, in small bedrooms lit by phone screens, it mutates again: Dazai as streetwear fusion with avant-garde layered styling trends, Dazai as an outfit you can live in when your insides feel too loud.

Fashion is a conversation too. It happens without permission. It happens like a confession muttered into a scarf.

I’ve watched kids board my last bus wearing long black overcoats that swallow their knees, but beneath that darkness: a flash of white shirt hem uneven on purpose, a harness strap crossing the torso like a map of tension, pants cut wide as a sail, boots heavy enough to make the floor feel it. They look like walking edits—erasures and additions. Asymmetry is not just a design choice; it’s a biography. One sleeve longer, one panel tucked, one side exposed: a body saying, I cannot balance the story, so I will wear it off-center.

Dazai’s spirit—mischief and melancholy stitched together—fits this. The streetwear part is the need to belong to a tribe without speaking. The avant-garde part is the refusal to let the tribe finish the sentence for you. Layering becomes a kind of armor that still breathes: oversized outerwear for distance, close-fitting inner layers for truth, accessories that read like punctuation—rings, chains, a stitched patch placed where a bruise would be.

The bus teaches me how clothing listens.

When someone sits down, the fabrics speak. Nylon swishes like a quick lie. Wool absorbs light and sound like a secret. Leather creaks like someone remembering something they promised they’d forget. A hoodie pulled tight changes the acoustics of a person’s breathing; it turns exhale into a tunnel. A scarf can muffle a name.

And the Dazai-inspired looks I keep seeing aren’t cosplay. They’re a translation. They take the bandage motif and turn it into wraps, straps, tape details—not as imitation, but as metaphor: I am held together. I am stylishly held together. They take the long coat and complicate it with cropped vests, uneven hems, layered shirting, dangling tabs. They take the formal and scratch it with street: sneakers under a coat that looks like it came from a theater wardrobe, a graphic tee peeking out like a grin at a funeral.

The city understands that contradiction. The city runs on it.

At 02:19, a girl in the second row lifts her phone and plays a song without earbuds. The bass is small and stubborn. The melody has that high, thin sadness that tastes like cheap black coffee. She’s wearing a deconstructed blazer—one lapel intact, the other replaced by a panel of matte fabric that looks like it was salvaged from a work uniform. Under it, a long shirt with side slits swings when the bus turns. Her socks are mismatched: one white, one black. She doesn’t look embarrassed. She looks intentional.

She catches me looking in the mirror and meets my eyes. For a second, I feel like I’ve been caught stealing. Then she smiles, barely, and looks away. Her perfume reaches the front—something citrusy cut with smoke, like an orange peeled in an ashtray.

I think of my own secrets.

There’s a tool I never leave home without: a small brass screwdriver, worn down at the tip, wrapped in a strip of cloth so it doesn’t rattle in my pocket. Most drivers carry a pen, a spare key, maybe a lucky charm. I carry that screwdriver because the old recorder’s battery door is cracked, and if it pops open mid-route the tape will chew itself into grief. The screwdriver came from a clock repair shop that used to stand near the depot before the landlord raised the rent. The old man there told me, without looking up, “Small tools keep big promises.” He died a month later. I kept the tool.

In my apartment, I also keep a cardboard箱—no label, no tape, just folded flaps like tired eyelids. Inside are failed recordings I never let anyone hear. Not because they’re embarrassing. Because they are too clear. A woman whispering goodbye to someone who wasn’t on the bus. A boy practicing an apology out loud, again and again, until his voice turned hoarse. A man singing a lullaby in a language my city doesn’t recognize, his notes trembling like a hand searching for a light switch in the dark. I tried to edit them once, to make something “beautiful.” Every time I cut the tape, the city’s breath felt wrong—like I’d interrupted a heartbeat.

And there is one cassette I have never played since the night I recorded it. It sits in a tin box with a dent in the lid, the kind you’d keep sewing needles in. On its label, in my handwriting, there is only a time: 03:03. That night, a passenger sat behind me and spoke my name. Not loudly. Not accusingly. Just… correctly. My name is not on my uniform. No one on that bus should have known it. The voice sounded young, but carried the weight of someone who had been waiting a long time. Then the person laughed—softly—and said, “Driver, you always listen. Do you ever let yourself be heard?” The tape clicked, like a throat closing. I drove the rest of the route with my mouth full of pennies.

That is what Dazai does to people. He makes listening feel dangerous, and necessary.

So when I hear “Dazai Osamu Bungo Stray Dogs Streetwear Fusion With Avant Garde Layered Styling Trends,” I don’t hear a keyword string. I hear passengers trying to stitch identity out of what they can afford: thrift-store coats, tailored knockoffs, handmade bandage wraps, safety pins that glint like tiny teeth. I hear them borrowing the elegance of despair and turning it into something they can walk in. I see them making an outfit that can survive a late-night bus seat’s rough fabric and still look like a poem.

The avant-garde layering—done right—doesn’t chase novelty. It stages a body like a city map: intersections, detours, closed roads. Asymmetrical hems mirror the way we all lean away from our pain while pretending we stand straight. Oversized silhouettes make space for secrets. Tight inner layers keep warmth close, like a withheld confession. Accessories become anchors: a chain for weight, a ring for reminder, a bandage wrap for a story that won’t fully close.

I know trend cycles. I watch them board and get off. One year it’s all clean minimalism, the next it’s maximalist chaos. But the Dazai-shaped thing keeps returning because it’s not just aesthetic; it’s a way of carrying contradiction without dropping it. It’s the romance of ruin—made practical. It’s a wink in the middle of a bruise.

Near the end of the route, the bus grows quieter. The heaters breathe hot dust. The windows fog and collect fingerprints like tiny ghost signatures. Outside, the city looks rinsed, emptied, waiting for morning to put its makeup back on.

A man in a long coat stands up before his stop. His layers shift: black outer coat, grey vest with an uneven cut, white shirt tail longer on one side, a strap crossing his chest. His hair is messy in a way that took time. He pauses by the front, close enough that I can smell rain on fabric, and says, “Thanks, driver.”

His voice is ordinary. His outfit is extraordinary. He doesn’t know I’ve recorded the way his gratitude lands—soft, almost shy, like a coin placed gently into a palm.

When he steps off, the bus door folds shut with a tired clap. The city swallows him. My recorder keeps turning, patient as an animal in the dark.

I keep driving.

Because the truest stories in this city don’t happen in offices or on stages. They happen in a moving box of light, after midnight, when strangers wear their hearts as layered garments and their loneliness as an asymmetric seam. They happen in the spaces between stops—where Dazai’s shadow can be a coat, a bandage, a joke, a wound, a trend, a confession.

And when the route finally ends, when the engine ticks as it cools and the depot smells like oil and damp concrete, I will take the cassette out with my brass screwdriver’s help, slide it into my pocket, and carry those voices home like heat.

Not to expose them.

To remember that under all the streetwear, all the avant-garde experimentation, all the fusion and styling and borrowed silhouettes—there is a living body, breathing in the dark, trying to be seen without being caught.